English can be a funny old language – but persevere and you’ll be speaking like a native in no time!

You’ve studied hard, planned your trip and booked your ticket to an English-speaking country. Here are some tips to surviving, learning, speaking English and enjoying yourself when you get there.

In our Spanish language article this month Diana is covering the survival language that people need when they arrive in a Spanish-speaking-country for the first time, so I’m going to look at the English you need for arriving in an Anglophone country. I’m saying English-speaking country to be more simple in the article, but many of these points will be the same if you go to Turkey or China, or wherever and are speaking English as your language of communication.

If you can read this paper, your English is probably good. Go and have a glass of Scotch to congratulate yourself. However, when you arrive in an English-speaking country, you will find that some things are different from the books. Also, even if your level is very high, there are other things that you need to be careful with.

Learning English in Colombia is a very different experience to living in an Anglophonic society. Here in Colombia you can stop speaking English when you leave class and in almost every situation you can communicate with people in Spanish. In an English-speaking country, that’s different. When you leave class, you have to speak English too.

It’s a good idea in general to have a support network in Spanish, but don’t rely on them too much. Try instead to make more friends with whom you can speak English. That doesn’t always mean British people, nor Aussies nor even Americans. For example, in London you’re as likely to talk to a Turk as an Englishman, and that’s really the wonderful thing about speaking English. It allows you to talk to everyone, not just native speakers.

I spoke to a colleague in the office who advised talking to old people and children. I wouldn’t have thought about that, but it makes sense. Children’s vocabulary is limited, they usually want to communicate and have inquisitive minds. Old folk are much more likely to speak slowly and they are often very kind. Best of all, they usually have a lot of free time to practise speaking to foreign learners.

It can be very good to find something that genuinely interests you. Maybe you are a fan of football, perhaps you play chess or breed hedgehogs. Joining a local club related to one of these things will make you lots of new friends and give you lots of new vocabulary. Best of all, that vocabulary is useful to you personally – which is what language learning should always be.

As well as making all these fun new friends, try and generally talk more than normal. For example, if you’re in the supermarket or the pub, try asking the server how their day has been. Talk to taxi drivers, they aren’t all like Travis Bickle. Especially, ask new people questions – this gives you listening practice, which is very important. It also gives you more cultural knowledge, which is surely one of the reasons you’ve moved to the place in question.

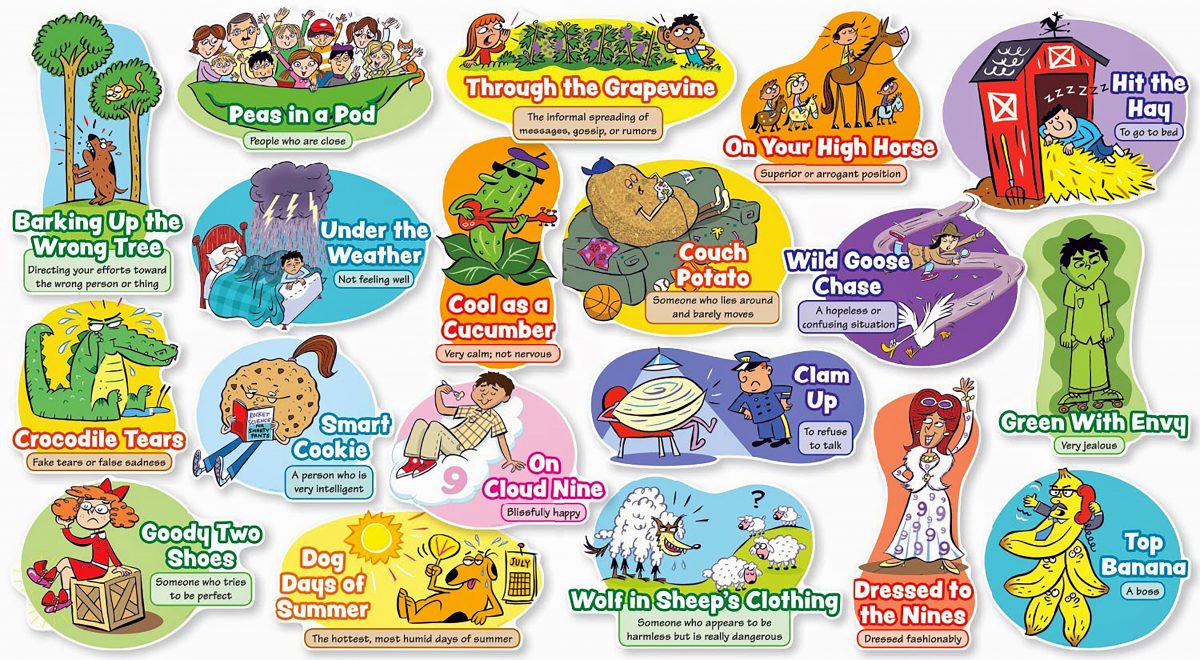

People will use a lot more slang in real life than most books prepare you for. Even if there isn’t too much slang, you might find that people use more diverse phrases than you’d expected. For example, you might notice that people use more than one greeting in the morning – try responding in the same way as they greet you.

Write down the new words you learn. Try to use them in new contexts, test them in real life. Don’t overload yourself, but do try and focus your language. I once spent a week in Tokyo deliberately overusing a certain grammar point. Someone said it was strange, but I explained I was learning. I still remember it too, after eight years.

Stop worrying about understanding everything. You’ll learn very quickly that communication is key. If someone says something you don’t understand but the context is clear, try responding to what you think they should have said. You might find that it works. With time will come more understanding.

We all make mistakes, even after years. It’s embarrassing the first time you realise, as I did, that excitar in Spanish doesn’t have the non-sexual meaning it has in English. The important thing is to not get depressed or shy. Learn to laugh when you make a mistake, but remember the embarrassment as a lesson. It’s true that people might laugh, but usually because they think it’s funny, not that you’re stupid. There are some people who will refuse to understand you. This can be because they have a mental problem with talking to foreigners, or they could simply be racist. Either way, smile, move on and forget about it.

It’s important to learn that mistakes are OK when you are speaking English, and for the same reason it’s important to say when you don’t understand something. People generally like to communicate, so they will probably explain or say it in a different way. It’s also important to ask for clarification – this is real life, not an exam and they will probably help you. It’s much better to ask for help when it’s not necessary than to not ask for help when it is necessary.

Of course, there will still be times when you have severe language problems. Google Translate and Word Reference are very useful tools for this. Be careful to make sure that you check the various different translations – not just the first one on the list. Other tactics to help here include mime, gesture and even drawing on pieces of paper. You might laugh – but I’ve done all three and it’s made my life easier.

All of this advice comes from the heart. It’s not all based on my experiences, but I’ve moved to both Japan and Colombia and solved language problems. I’ve stood in a Kazakh market and managed to work out what was in the pies. If a well-meaning buffoon* like me can do it, so can you!

*not that well meaning at all.