Pedro Luís: “The situation in Venezuela is hard. There is hunger, there aren’t any jobs, there’s nothing. We have been hitchhiking for six days from Cúcuta.

As thousands of footsore caminantes walk from the Venezuelan border to towns and cities in Colombia – and beyond – in search of food, medicine and shelter, we speak to some of the arrivals in Bogotá.

These are their stories of Frank, Gabriel, Juan Carlos, Pedro Luís, Johny & Joana and Alejandro & Ernesto.

Part two of stories from caminantes.

– Interviews by Steve Hide, Todd Wills, Sarah Lapidus and Daniel Mateus

– Photos by Steve Hide and Daniel Mateus

Frank Frank

Frank is from the capital Caracas where he worked as a policeman but had to quit because his son was seriously ill. He has walked most of the week-long journey from the border with a close friend, where he described the temperature in the páramo as bone-chilling, so much so that he fainted at one point. He was hoping to travel onwards to Peru to meet with his sick mother, however he now feels he will stay in Colombia and meet his mother here instead.

“I used to be a cop in Caracas, when the crisis wasn’t that difficult. If I wanted to go back to Caracas, I could be tried for treason because I asked for early retirement to look after my ill son. I left Venezuela because of the lack of basic necessities and essential products. The journey between Cúcuta and the Páramo de Berlin was the most difficult: I fell from the bus because it was so cold. I cried the first time I was offered a tamal by a stranger, because it was the first time I had eaten one in a year. I have experienced xenophobia here from the authorities. Sometimes people come into the camps at night and kick and yell at us.”

|

Gabriel Sánchez

24-year-old Gabriel Sánchez, who was raised by his grandparents and studying occupational therapy, had tears in his eyes as he spoke of the difficulty of leaving his family. After being robbed, he had no money and was waiting at the encampment until he could get a ride to Salado.

“I had to leave for my family. My grandpa needed medicine, which we didn’t have. I came here on foot from Cúcuta. Someone who posed as an asesora stole my COP$300,000. I am here fighting for my grandparents.”

|

Juan Carlos Juan Carlos

Juan Carlos from Ciudad de Valencia has been here for one year. He has benefitted from the PEP, a special permit allowing Venezuelans to stay and work in Colombia for two years, and is grateful for his good boss and his job as a parking lot attendant in Soacha.

“We were dying of hunger there. Thank God I have a very good job. I arrived here without a permit. I became registered and have a good job with a good boss. But now, they fine people without permits. They’ve shut the registration [for PEP],” he said.”

|

Pedro Luís Pedro Luís

Pedro Luís, a former bricklayer in Venezuela, has been walking and hopping on the back of big rigs with three long-time friends en route to Peru. He left his two children and wife in Venezuela because of the hunger and lack of jobs. He hopes to send them money when he finds a job. One of Pedro’s friends, Oswaldo, said the hardest part was at night, not knowing where to sleep. “Last night we slept under the porch of a bakery. Someone even stole my shoes.”

“The situation in Venezuela is hard. There is hunger, there aren’t any jobs, there’s nothing. We have been hitchhiking for six days from Cúcuta. Here they have treated us better than in Venezuela. They help us out when we are hungry and thirsty. People see that we are coming on foot and they call us over, offering us a small coffee, a piece of bread, or a soda. Then, we sit, exhausted. We travel from town to town until nightfall. The hardest part about the trip was the cold, especially when we were passing Tunja.”

|

Johny and Joana

Johny and Joana had been travelling for four days by bus and were on their way to stay with family in Peru where they say there is more opportunity for work. They had been planning to leave for the past year, waiting until they saved up enough money for this trip. They left their six-year-old daughter in Venezuela. We caught up with them at a bus station in Soacha, south of Bogotá.

“In Venezuela the public forces have turned against the people. We don’t have medicine, doctors, or teachers. You can’t even get meat. You have to pay [for passports] in dollars.”

|

Alejandro and Ernesto

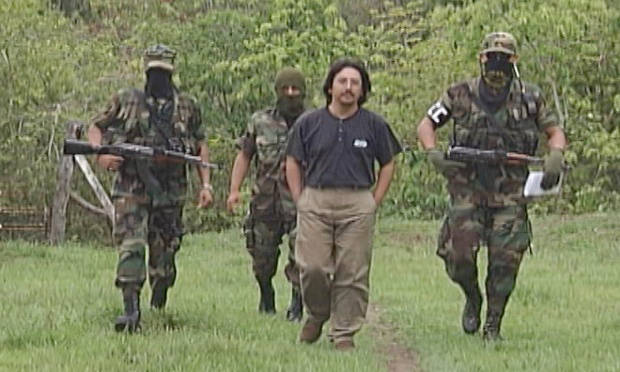

37-year-old Alejandro, who worked as a bodyguard for government personnel, and 44-year-old Ernesto, who used to work for the army, are both in Colombia escaping from political persecution.

Alejandro: “I didn’t support the things the government was doing like corruption and drug trafficking. They are looking for me. They already attempted to kidnap me. Don’t believe what the government is telling you. In Venezuela, there is no life. Now, there is nothing.”

Ernesto: “I had no choice but to leave because I denounced the corruption in the military. They were stealing building supplies (copper tubing, doors, etc.) and not giving them to the people that needed them the most.”

|

Frank

Frank Juan Carlos

Juan Carlos Pedro Luís

Pedro Luís