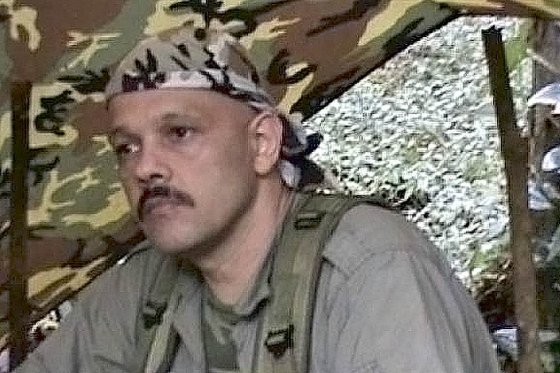

Hernán Darío Velásquez, alias “el Paisa”

On April 24, FARC commander Hernán Darío Velásquez, also known as El Paisa, arrived in Havana.

Accused of numerous crimes as commander of the guerrilla’s violent elite unit Teófilo Forero, the presence of El Paisa in the Cuban capital is not welcomed by all. President Santos admitted to Caracol Radio that he felt a “bittersweet sensation” upon learning that one of the most wanted FARC combatants would join the delegation. Although it is certainly controversial, El Paisa’s presence in Havana is also reassuring, because it means he is not “committing atrocities” in Colombia, and it clearly demonstrates the FARC’s commitment to the process, the president said.

Peace delegations reconvened in Havana on May 4 in an effort to break the impasse on issues related to the FARC’s demobilisation. The controversial issue of “concentration zones” continues to stall conversations, and no major announcements have come from either side of the negotiating table since they failed to meet the deadline for the signing of a final peace accord in March.

The peace delegations also continue to be divided on the last item of the agenda, “implementation”. Surprisingly, a vital step towards solving this issue was not made in Havana but on the domestic front: outgoing attorney general Eduardo Montealegre filed a petition to the Constitutional Court on March 28, demanding that the peace agreement be conceived as an international humanitarian treaty. This would automatically bestow constitutional status upon the agreement and make its implementation legally binding to all political institutions and future administrations, regardless of their political agenda. The petition has been admitted by the Constitutional Court, and if granted would likely render obsolete the government-led efforts to hold a plebiscite and the legislative framework for peace to implement the agreement, since neither instrument is competent to amend constitutional norms.

Meanwhile, government negotiator Humberto de la Calle seriously questioned the petition filed by Montealegre, affirming that “the negotiating parties do not have the power to reform the Constitution.” According to de la Calle, any discussion regarding the legal status of the peace agreement cannot bypass Congress or any other national political institution, let alone the obligation to seek the approval of the Colombian people.

With little progress made in Havana, people are becoming increasingly pessimistic about the prospects for peace in 2016. According to the latest Gallup Poll, only 28% believe a peace deal will be reached this year.

Veronika Hoelker holds a Master’s degree in International Relations of the Americas from UCL and currently works at the Bogotá-based NGO the Permanent Committee for the Defense of Human Rights. Veronika assists the judicial advisers at the NGO in matters related to transitional justice and the Colombian peace process in general.