Protests will take place throughout the country today, in spite of COVID-19 concerns.

It’s eleven months since the dramatic national protests of 2019 and just six weeks after the demonstrations following the police killing of Javier Ordóñez that ended violently. This week, Colombians again take to the streets to demonstrate their discontent.

Protests will take place throughout the country, including Bogotá, Medellín, Barranquilla, Armenia, Manizales and Cúcuta. The Bogotá demonstrations will gather at the usual meeting points such as the Universidad Nacional, the Parque Nacional, Parque Olaya, Parque de la Sol, La Sevillana and Héroes from around 10am.

Who’s striking?

Today’s paro nacional — national strike — will be joined by Fecode, the national union of education workers, and the minga indígena. Fecode began a 48-hour strike yesterday with various workshops, online forums and conversations. The minga indígena includes around 7,000 indigenous people from Cauca and nearby, activists, Afro-Colombians, and campesinos who arrived in Bogotá on Monday and will leave today.

Why are people protesting?

Many of the concerns that drove people to protest 11 months ago have only intensified since then. The six-month coronavirus lockdown has had a drastic economic impact, increasing unemployment and putting pressure on the country’s health system.

In addition, we’ve seen an increase in violence against social leaders and armed group activity. The quarantine measures taken to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus left isolated communities even more at risk from armed groups looking to consolidate power.

The International Crisis Group recently reported that at least 415 social leaders have been killed since the peace accord was signed, stressing that the violence has only increased during the pandemic.

People on the streets today will protest against many issues, including the economic and social situation, police violence, social leader assassinations and rising unemployment.

COVID concerns

Some, like Bruce Mac Master, the leader of ANDI (Colombia’s business association), have criticised the protests because of the increased risk of coronavirus contagion. On Monday, President Iván Duque tweeted about “the importance of preserving health and avoiding gatherings that put Colombian lives at risk.”

In contrast, Bogotá’s mayor Claudia López thanked the minga participants for their compliance with both biosecurity and security measures. She later called on the government to support the indigenous marchers to guarantee a “biosecure return to the reservations.”

The minga indígena

The term minga comes from an indigenous Quechua word: mink’a. It encompasses a sense of community and common purpose. A minga can be called to bring people together towards a goal, in this case, to demand a right to life, territory, democracy, and peace.

Last year, the Guardia Indígena of Cauca created quite a stir when they joined the protests. The presence of some indigenous groups added weight to the demonstrations and also strengthened the peaceful nature of the protests.

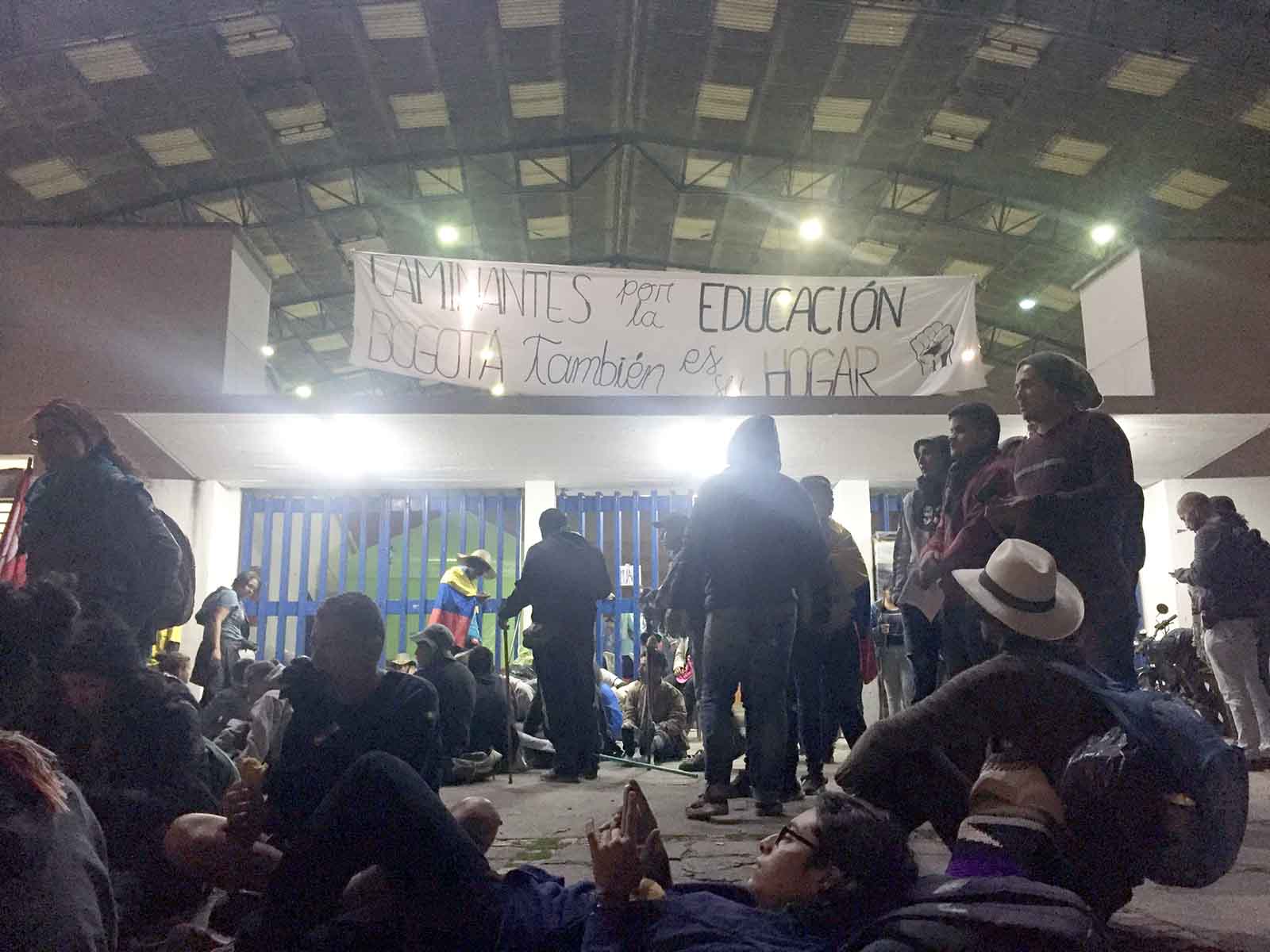

This year, the groups have stayed in the Palacio de los Deportes during their three days in the capital. They travelled from various parts of the country to demand a meeting with President Duque — a demand that was not met in Cali, although Interior Minister Alicia Arango arrived and was ignored.

The minga want the government to fulfil its obligations under Colombia’s peace agreement. They protest against the continued killing of social leaders and the increasing violence in many rural areas.