An attack on a TV station live on air made world headlines, but tension in Ecuador has been bubbling away for a while now. The young new president, Daniel Noboa, is looking to emulate the so far successful crackdown on crime by Nayib Bukele in El Salvador.

While Bukele’s ultra-strict approach to breaking the gangs has won him the contempt of international human rights’ organisations, it’s wildly popular with actual Salvadoreans who can finally walk the streets without fear. Last weekend he “pulverised” the opposition while emphatically winning re-election. (His words, not ours.)

Noboa’s proposal for mega-prisons reflects skyrocketing crime in Ecuador. Just six years ago, the murder rate was a mere 5.7 per 100,000, lower than the global average, let alone the region. Today, it stands at 45 or even higher per 100,000. The big game changer was cocaine and its cartels.

This was also true in Mexico, where changing drug distribution routes caused the Jalisco New Generation armed group to grow quickly in both power and prestige. Mexico went from being relatively safe by Central American standards to having the world’s most violent cities (outside war zones).

However, this is only part of the puzzle. The real key factor is weak and unbothered states. Both Mexico under AMLO and Ecuador under Lenin Rojas simply ignored or downplayed the signs pointing to increased crime, allowing it to balloon. Once a country has shown that crime pays and no effective action will be taken, the problem snowballs, particularly when there are few other opportunities.

Ecuador added a percentage point to its murder rate for two years running, before starting to nearly double year on year. Crime cartels become more powerful. This made it harder to crack down and also encouraged new entrants, attracted by the lack of consequences.

At that point, drastic measures become necessary – enter Nayib Bukele. The self-styled ‘world’s coolest dictator’ has made the country functional and enjoys the adoration of his people. Even if it may not be sustainable in the long run to lock up 1% of the population, it’s no surprise that other regional leaders are considering copying his approach.

Where is Colombia now?

Well, first the ‘good’ news. Part of the reason for Ecuador’s descent into chaos is that said chaos was leaving Colombia. It’s also true that Colombia is starting from a much higher position in the homicide charts and that the country’s long-term crime rates have fallen, despite a recent uptick.

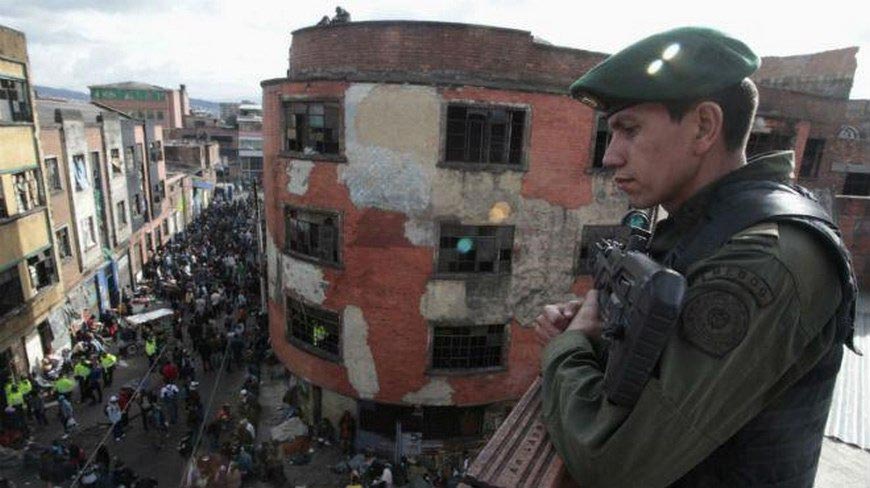

However, there are some similarities. As in Ecuador, crime is both creeping up and being normalised, while neither police nor military are taking any effective action. It’s starting to make waves in the news, especially in Bogotá. This is a pot that’s bubbling ever more on the back burner.

Kidnappings are back on the mainstream agenda and killings continue, especially in the countryside. Extortion is on the rise and there are more and more reports of brazen attacks within Bogotá and other urban cities, from public buses being held up to restaurants being invaded. Various organised crime groups such as the Tren de Aragua operate in the capital.

Colombia has a long history of not nipping things in the bud and then having to clean up a bigger mess, sadly. Recently, authorities scoffed at reports of fentanyl entering the country and beginning to circulate and insisted it was all a storm in a teacup. Unsurprisingly, it’s now becoming obvious that there is indeed a lot of fentanyl in the country and now we’re scrambling to react.

Or look at the Choco landslide in January, despite repeated warnings that such an event was possible. Cast your mind back to when Mocoa was hit by a similar disaster in 2017. Note how El Niño wasn’t prepared for, leading to spates of wildfires. These are tragedies not just foretold but telegraphed years or even decades in advance.

These problems are most visible when they hit the headlines in dramatic events such as storming a news station or a landslide annihilating a city. But they are set up much earlier. Acting before the situation is critical saves time, money, and lives in the long run. It also requires foresight, planning, and investment for the future.

Those three things are in sadly short supply though and the real fear is not that some big tragic event will hit the headlines but that simply nothing will be done. A failure to act now and get crime under at least some sort of control sows the seeds for surefire tragedy later. Unfortunately, no arm of the state seems in any way willing to act at the moment.

Worst of all, that failure to act with reasonable measures now means that unreasonable measures become more palatable to the general public. Levels of concern over violence and crime trump everything else for many voters and if the options are extreme crackdowns or nothing, many will take the former.