According to Colombia’s Ombudsman’s Office, 196 social leaders were killed between March 2018 and May 2019. Speaking at the installation of a new congressional term last week, President Iván Duque gave evidence that violence against social leaders had decreased. The same day, three different social leaders were killed in different departments across the country, reported Pacifista.

Recently-released statistics from the Presidential Council for Human Rights — which differ largely from those obtained by the Ombudsman’s Office — indicate that social leader killings have reduced by 32% under Duque’s governance.

Miguel Ceballos, Colombia’s High Commissioner for Peace, attributes this to protection measures put in place by the Opportune Action Plan (PAO), he told journalists at this year’s OAS General Assembly, held in Medellín.

Installed in November 2018, the plan aims to protect human rights defenders, social leaders, community leaders and journalists. Headed by the Ministry of the Interior, it is also supported by the country’s justice ministers, Ministry of Defence and the Office of the Attorney General.

Prior to this, measures to protect social leaders had already been put in place by the 2016 peace accord, which contains its own specific clause offering security guarantees for leaders of social movements and defenders of human rights.

Speaking to journalists, Ceballos confirmed that the Colombian government holds three groups accountable for crimes against social leaders in Colombia, all of which include either current or former insurgents. The first group he identifies are dissidents of the FARC left-wing guerrilla group, followed by members of the Clan del Golfo, a right-wing paramilitary organization, and lastly, members of the ELN, the leftist guerilla group.

The government, in the plan, has identified departments that are particularly at risk for social leaders, which currently comprise Antioquia, Cauca and North Santander, closely followed by Valle del Cauca, Nariño, Caquetá, Chocó and Córdoba.

The plan consists of three strategic pillars around which the government pledges to organize the protection it provides for social leaders: strengthening interdepartmental responses to crimes, intervening strategically in territories and working on strategies to ensure the non-stigmatization of social leaders.

The 39-page document contains clauses that pertain to improving specific bodies within the police force in areas of security and investigation, and increasing the presence of military personnel in certain parts of the country.

It also details responses to the Early Alert System that warns social leaders of the risks they are facing, which is managed by the Ombudsman’s Office and was put in place by the peace accord. Responses include extra security and protection measures for leaders, — such as escorts — attention for victims and vulnerable populations, special gender and ethnicity-focused attention, a system to prevent the recruitment and abuse of minors, prevention of sexual violence, and the substition of the use of illicit crops.

The PAO also attempts to identify the reasons for which social leaders are currently being targeted, attributing violence to territorial disputes over illicit economies. These conflicts are fueled by competition to plant illegal crops such as coca, carry out illegal mining and other illicit activities.

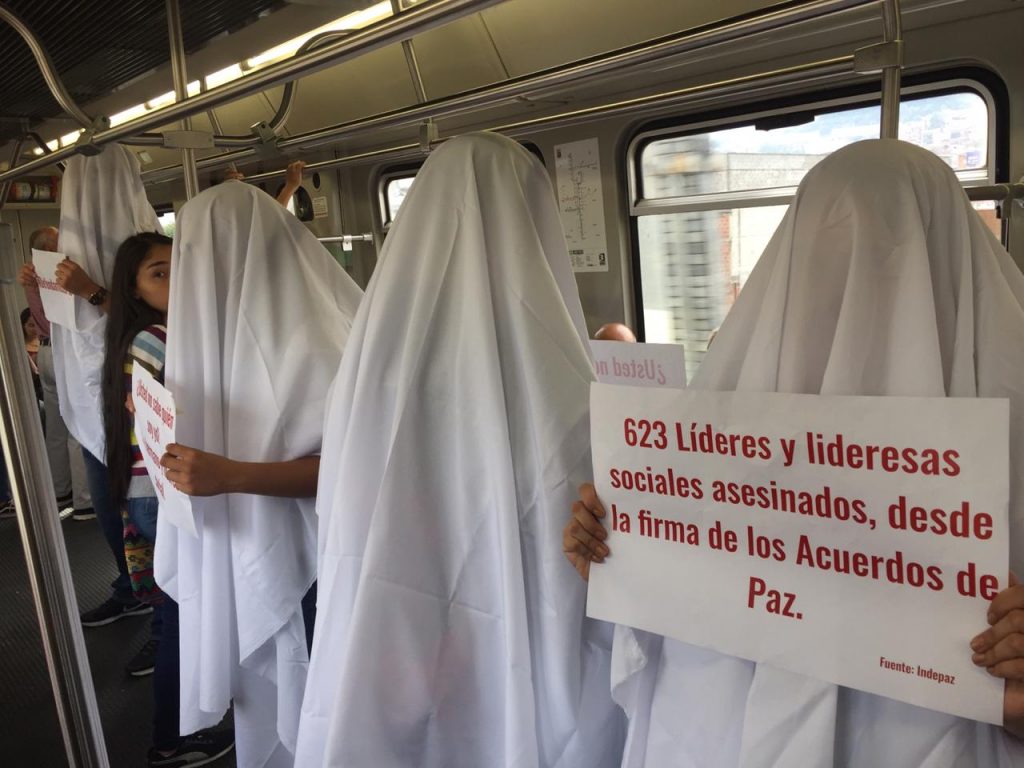

According to research carried out by Bogotá-based peace-building NGO Indepaz, 623 social leaders and human rights defenders have been assassinated in Colombia since the signing of the peace accord in November 2016. During this time period, two sets of government-led measures were put in place to ensure their protection.

This article originally appeared on Latin America Reports.