Colombia’s Finance Minister, Mauricio Cárdenas – World Economic Forum on Latin America 2010. Photo: World Economic Forum CC BY-SA 2.0

Up until recently the country’s economic engine had been roaring, but falling oil prices means the economic outlook for 2015 is uncertain

“It’s been a pretty horrendous run for Colombia,” Edwin Gutierrez, who helps manage $13.5 billion in emerging-market debt at Aberdeen Asset Management Plc, said in a telephone interview from London. “You find out these countries are a bigger oil story than you thought, once oil tumbles by half.”

Basically, with the price of oil plummeting, the year ahead is not looking so rosy for emerging economies like Colombia, no matter how sound the fiscal policy might be.

The dramatic drop in the price of crude oil has affected economies all over the world. From a high of $100 USD per barrel last year, prices have now fallen to just over $48 USD. Some countries, including Colombia’s neighbour Venezuela, have felt the pain even harder.

Despite not considering itself an oil economy, Colombia is far from immune to the hit. The Colombian government was forced to increase taxes this year, facing a budget shortfall of $6.5 billion USD caused by falling oil prices.

Colombia’s Finance Minister Mauricio Cardenas said this week that “We are well prepared [for a fall in oil prices], although that does not mean we are absolutely shielded.” He also said in an interview with Bloomberg in December that oil accounts for just 16 percent of the central government’s revenue.

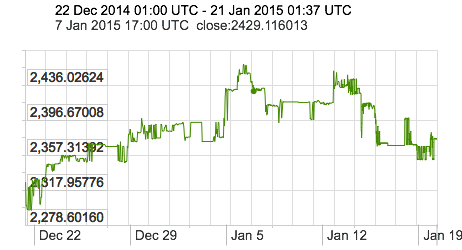

- Colombain Peso

- Curde Oil Price

But the fact remains that the Colombian peso is currently one of the worst-performing currencies in the world. This makes for a very different picture than last year, when state oil company Ecopetrol was briefly the most valuable company in Latin America and the peso the most valuable currency. Now, Ecopetrol has lost three quarters of its market value, and the peso has fallen 15 percent.

This situation causes a number of problems. Firstly, the dramatic drop in the price of oil means that Colombia’s original 2015 budget is no longer worth the paper it was written on. The country made assumptions on earnings based on a price of oil which no longer applies. This has been adjusted for by raising taxes to plug the budget deficit, but analysts are already saying a further tax hike may be necessary if the price of oil continues to fall.

Secondly, although Colombia is not an oil economy in the same way as, for example, Venezuela, oil still accounts for a large portion – over 50 percent – of the country’s exports. If prices stay low in the long-term, the country will be forced to adjust the peso and cut public sector spending to make up for the sudden loss of income.

Why have oil prices fallen?It is essentially a question of supply and demand – the demand has been shrinking in Asia and Europe because of economic factors, increased environmental efficiency and a move towards other fuels. At the same time, a high oil price allowed countries like the USA and Canada to increase their production with fracking and horizontal drilling. As Libya and Iraq return to the market after conflict reduced their production, increased supply with a weakening demand forced prices down. |

A spokesperson for Ecopetrol told The Bogota Post: “You can see the world economy is not going to grow at the same rate as it did in previous years.”

The spokesperson added: “Particularly in Colombia, growth is going to be less supported by the hydrocarbons industry thanks to the fall in international crude prices, which is not expected to recover in the short term.”

Thirdly, as the peace process continues, questions are being raised as to where the money to fund an ambitious demobilisation programme will come from. A year ago, the answer would have been obvious: oil revenue. But now that option is far from certain.

Despite all of this, Colombia’s economy is still predicted to grow 4.2 percent this year, more than double the regional average. The country has the option to issue more foreign debt and fiscal policies such as adjusting inflation mean there are contingency plans available. But for investors and citizens, 2015 may not be quite as bright as 2014.