Maxim Februari. Photo: Chris Rijksen

We sit in the sumptuous surroundings of Holland House, waiting for Maxim Februari and Brigitte Baptiste, someone becoming a woman to interview someone becoming a man. Neither of them were born that way; both know it to be something they must do. It’s often seen as a very controversial or daring subject, but at its heart, it is a simple one of human desire. To be what you want to be. It seems crazy to me that anyone would find a problem with someone else wanting to be happy, but problems abound in our society, obsessed as it is with the actions of others, even when they affect us so little.

Brigitte comments that in Spanish it’s always very obvious which gender you mean, as the language itself highlights that, which isn’t true in English. Max agrees that this makes things easier, and points out that gender is not inherently necessary in language. An important part of gender has always been separating the natural from the created. There are cultural aspects to gender that are not in any way part of nature. Max comments that “nature doesn’t make lines”, that in fact “it is we that create lines and divisions. Nature in fact, usually rejects lines and difference and attempts to make everything the same”.

The fact that both Brigitte Baptiste and Maxim Februari have experienced life as two different genders gives them a unique insight to gender roles. Max sees this as an often humorous aspect of the change: “I had heard that many Colombians think transexulaity is a part of homosexuality, which they are not. The first has to do with your identity, the second with whom you love. Transexuality is often seen as a serious thing, but there are many funny aspects to it. We laugh a lot at the changes that happen – you start off in homosexual relationships, then move to hetero ones…I went from being a lesbian to a straight man. There are so many stories from that, I got mixed up myself…a very funny experience indeed”.

It is not all funny though – Max explains how strange it was to experience being a man and have “the privileges of being this nice gentleman. When I became a man I became someone that people had to respect, to take seriously, to listen to I remember my first meeting, that all I had to do was speak and people would instantly listen”. Many of us understand that gender imbalances and bias like this exist; few of us have experienced both sides of it.

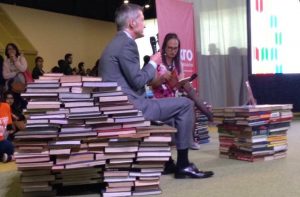

Maxim Februari and Brigitte Baptiste speaking about the construction of gender. Photo: FILBo

One would think of Dutch society as being light years ahead of the world, coming as they so often do at the top of every development index, but it’s not all rainbows and unicorns, according to Februari “it might surprise you about Holland, as everyone sees us as this advanced, free thinking society. There are more transsexuals than many places, but also it is more sexist than you might think. It is conservative too, and Dutch society can be very hard to fight sometimes.”

At the heart of all this is the importance of feminism, a fact that Februari acknowledges implicitly. Recently there has been a lot of debate over the place of transsexuals in the feminist movement and Max refers to this “I was accused, when I started my transformation, of betraying feminism. Maybe though, I have become more feminist throughout my transition because I have seen the differences and the problems from both sides. I promise you, I have become more of an active feminist now I have had these experiences”.

Max notes the different attitudes towards male-female and female-male transsexuals. “in fact, the problem is not violence against transsexuals. It’s violence against women, in another form. The journey is not important to these people, it is just another woman to attack. I pass easily as a man, maybe a little feminine, but I really experience very little aggression. It’s very much more difficult for trans people going the other way, that they are seen as easier targets, more obvious. But the problem, again, is violence itself, especially against women.”

“Everyone is playing with the idea of femininity,” says Max. He explains how “women get plastic surgery to augment their bodies, they put on make-up, wear dresses and perfume. Maybe not as much in the Netherlands as here, but everyone is trying to find their femininity. It’s not just trans people doing it.” The irony of these words is that sidestage, a Canal Capital presenter is busy conforming to a male ideal as she preens and pouts in preparation for an interview.

Masculinity, too, is becoming confused. Traditional male roles are becoming less so, and there is a growing swell of confused young men who are adrift in the world without role models or clear lines on what being a man is. This is a chance for experimentation and discovery, yet is often presented as a crisis. Max advises that “we are being forced to be extremely beautiful and maybe we should go back to looking the way we look, dressing the way we would like to dress and forgetting about what other people want us to do. It should be OK for boys to be more sensitive and this whole idea that men need to go back to the woods is just absurd.”

The only shock for Maxim Februari comes at the end, when he comments on how many good things he has heard about Brigitte and that he has seen few signs of problems with transsexuals. She puts him straight fast, mentioning expulsions and social cleaning. However, she also tells him that it has got better in the past few years.

Two fascinating journeys being undertaken by two erudite speakers and one fine conversation. It is something that so few of us question, and maybe we should. Perhaps the prefix cis- should be used more often, to remind us that what the majority do or think isn’t necessarily normal or correct, but simply the mainstream view. A short chat here in Holland House has made all of us in the audience a lot more aware of gender issues and how fluid they can be in reality.