By Marvin Vivas & Natasha Pentin

Nearly two months after emerging from the Amazon, three Colombian Special Forces soldiers reflected on their ephemeral fame after rescuing four Indigenous children aged 11 months to 13 years. Following a single-engine Cessna plane crash that killed their mother and everyone else onboard, these kids were lost in the jungle and survived for 40 days in the thick wilderness.

“Yes, we took the photo of the children that circulated the world. But we didn’t know the impact it would have,” the soldiers told The Bogotá Post. “Usually, the jobs we do happen in silence. It’s the first time [the Ministry of Defense] took us in front of the public like this.”

The soldiers—who agreed to an interview only if we used pseudonyms to protect their identities due to the dangerous nature of their work—spent 19 days in the dense jungle between the southern departments of Caquetá and Guaviare, searching for the four children from the Uitoto Indigenous community.

The mission, dubbed “Operación Esperanza” (Operation Hope), captivated the nation—and soon after, the world—when the children, malnourished and disorientated, were found by a group of Indigenous guardsmen who worked alongside the military to track them down.

The story was covered by the largest international media and was claimed as a win by Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro. Film producers have flocked to Colombia to negotiate with the family of the children for the rights to the story—a process that has been complicated due to a custody battle between the father of the children and the family of their deceased mother.

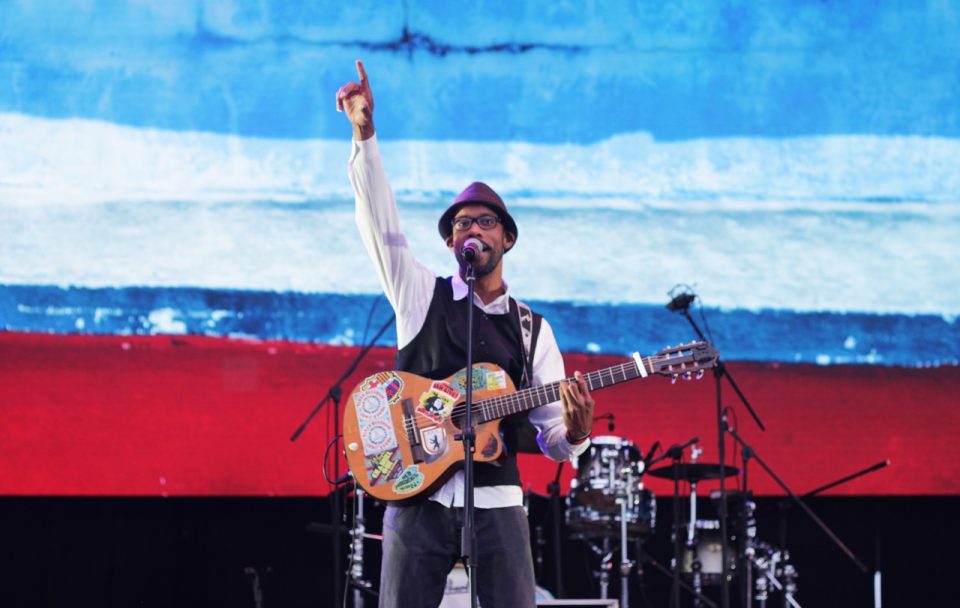

At first glance, the soldiers could have been anybody; dressed in jeans, tops, and fanny packs, glued to their phones, texting family members and friends. In fact, these soldiers are visibly outside of their element at a dinner following a Festival of the Flowers parade in Medellín, where their work was celebrated.

Apart from a few small scars, presumably from previous missions, the signs of being in the jungle for 19 days with the pressure of a nation on their shoulders were barely noticeable. All the same, they’re not quite used to taking selfies with fans yet.

The Colombian military has many faces. Some view them as heroes who track down guerilla insurgents and drug traffickers in the most isolated regions of Colombia. Others see the military as one of the largest human rights abusers: During Colombia’s armed conflict, the ‘false positives’ scandal saw thousands of innocent people killed by some members of the Colombian army and falsely labeled as guerillas. And distrust in the institution has risen in the past few years.

For this reason, we can see why these four soldiers see the publicly visible celebration of their work as heartwarming. “It is gratifying to feel the support of the majority of the Colombian people,” said a soldier we’ll call Orlando. Despite this, though, the official narrative surrounding the rescue has been challenged, and Orlando recognizes that there are “positive and negative points” about being in the public eye.

“Not everyone thinks the same about the operation,” he said. “For example, there are some theories that the children were held by the dissidents of FARC [Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia] or the Indigenous people. Some claim the children were never lost. However, we know from the front line that they were because the conditions we found them in were inhumane,” said Orlando, addressing different narratives about the rescue.

Working with the indigenous and respecting their traditions

The mission to find the lost children was notable for many reasons, one being the collaboration between Colombia’s military and members of the Indigenous community, who have been disproportionately affected throughout Colombia’s decades-long armed conflict, including by the military itself.

Facing the challenge of navigating the dense jungle, members of the Indigenous Guard, from areas like Popayán, Puerto Nariño and Florencia, were invited by the military to help find the missing children.

For the soldiers, it was an immersive lesson about Indigenous plant medicine, mystical beliefs, and ancestral practices, and an opportunity to also share with the Indigenous Guard some of the latest military technology, like satellites and radios.

“They had their beliefs, and we had ours. But we all focused on the same mission and purpose: to find the four children alive,” said Orlando.

The soldiers described how when the Indigenous Guard finally found the kids, they blew tobacco smoke onto them, since, according to the Uitoto elders, the jungle spirits or “duendes” had been hiding them.

Another soldier, who has Indigenous roots from the Amazon, said he tried some of the Indigenous Guard’s “mambe,” a powder made of toasted coca leaves mixed with the ash of Yarumo leaves. According to a member of the Indigenous Guard, they used the medicine during the search to help orient themselves in the forest and “decipher the mysteries that the mother jungle hides.”

The soldiers said they didn’t expect to work with the Indigenous Guard again, unless it was on a humanitarian mission.

Near the time of the rescue, Rufina Román, an Indigenous leader from Colombia’s Amazon, told The Christian Science Monitor: “This was a lesson … to look for commonalities … We are going to need to rely on joint action for many other issues [beyond this plane crash] that come at us, like climate change.”

Back to the jungle, back to their comfort zone

Throughout our chat, the soldiers kept referring to the mental fortitude of the team when facing dangerous operations. “One does not abandon the ship,” said Jorge, who spent six years in Catatumbo, a region heavily contested by illegal armed gangs and ELN guerilla fighters. “The most important thing is to do the work with love; with love for the country,” added Jonathan.

Despite their tough exteriors, one part of Operation Hope seemed to impact the soldiers: the feeble condition of the children before they were airlifted out.

General Pedro Sánchez, the Joint Commander of Special Operations of the Colombian Military, who led the mission to find the children, told The Bogotá Post: “As well as being a special operation, the other motivation was that the majority of the team are fathers too.” Jonathan has two children under two years of age and Jorge has a daughter who is about to turn seven.

For the soldiers, the clamor surrounding the mission to find the missing children may be a passing occurrence, as the fighters were to be shipped off the next day to a new location for another mission.

“It was a job that we were called to do during that time and, now that it’s over; we are preparing for other types of missions,” they said.

“It’s not our first time in the jungle,” Jorge added with a smile. “It is our comfort zone.”