Justice for George Floyd, Justice for Anderson Arboleda: Black Lives Matter in Colombia

On May 19, police in Cauca are alleged to have beaten 24-year-old Anderson Arboleda, who later died from his injuries. The reason? Arboleda had been suspected of breaking the department’s strict quarantine curfew. Just six days later in the United States, Minneapolis Police Officer Chauvin killed George Floyd by kneeling on his neck for eight minutes and forty-six seconds. As the United States and the rest of the world turn their attention to #BlackLivesMatter, Colombian artists and activists have highlighted the case of Arboleda: a horrific death of a young, Black, Afro-Colombian, unarmed man at the hands of police.

Bogotá saw a major Black Lives Matter protest on June 3, when various groups gathered in front of the U.S. Embassy to protest police brutality and the deaths of black people transnationally. One group burned a U.S. flag; others carried signs with slogans such as “ACAB, #BlackLivesMatter”, “Justicia para George Floyd,” and “Anderson No Murió, Anderson Lo Mataron. ACAB.” The signage highlighted the global nature of police violence, an issue that was central in the paro nacional as many criticised the government for its harsh treatment of protesters.

Similar demands were seen following ESMAD’s killing of 18-year-old Dilan Cruz. But unlike the national strike, the June 3 protests centred Black and Afro-Colombian voices and highlighted Colombia’s violent form of anti-Blackness.

Media silence

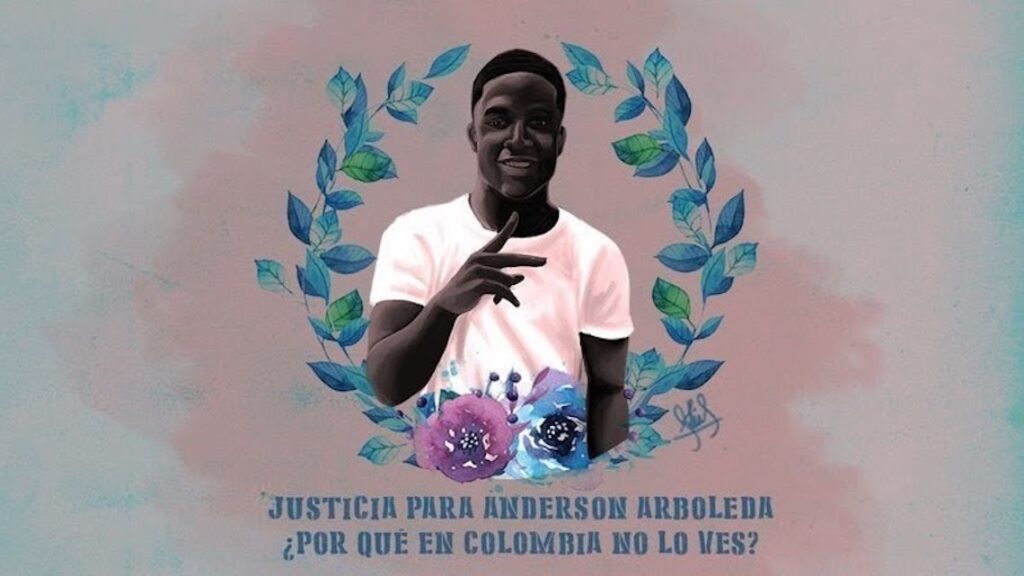

ChocQuibTown’s Goyo, the first major musician to denounce Arboleda’s killing, wrote “Racism is when police murder a young [Black man] in Puerto Tejada supposedly for failing to comply with the quarantine. And this isn’t reported by big media outlets. Is this not enough to outrage a country?” J Balvin quickly followed suit, publicly demanding an investigation. An illustration of Arboleda surrounded by a wreath (echoing the viral, memorialising portrayals of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery) has circulated on Instagram. “Por qué en Colombia No Lo Ves?” reads the post.

Aurora Vergara, Director of the Center of Afrodiasporic Studies at Universidad Icesi, told La Silla Vacia, “It’s not recognized that the foundation of the Colombian nation we know today derives from a system of slavery. And this doesn’t allow us to recognise that in 169 years the conditions of these human beings that are descendants of those that were enslaved have not changed much.” While Colombia’s history of slavery and development of race is distinct from that of the United States, Colombia’s own history of racism can be seen in police brutality towards Afro-Colombians and the assassinations of many Afro-Colombian social leaders.

Read our latest coverage on the coronavirus in Colombia

Vergara continues, “For Colombia, George Floyd leaves the messages that racism kills, and it kills in different ways.” She cites the fact that Black men in Chocó, have the lowest life expectancy in the nation. Afro-Colombians overall see a lower life expectancy and an infant mortality rate three times the national average.

These inequities in health connect to a widespread devaluing of Afro-Colombian lives, exacerbated by poverty, the armed conflict, displacement, and access to government services. While Afro-Colombians represent a quarter of the population, they make up almost 80% of those living in poverty. More than 30% of Afro-Colombians have no water and sanitation services. The Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) argues these statistics can be attributed in part to disparities in land access. WOLA’s 2015 report on Afro-Colombians also found that many Black workers were regularly exploited for their labour, and ESMAD’s efforts to negotiate labour disputes have ended in violence wreaked upon those same exploited workers. “Colombia is officially a plural-ethnic country, but it is not treated that way,” wrote the authors.

Afro-Colombians remain invisible

Colombia is home to the second-largest Black population in Latin America, but Afro-Colombians remain largely invisible in media, politics, and other positions of power. Only recently has “Afro-Colombian” been seen as a political and racial category; in 1993, when Afro-Colombian was introduced into the census, only 1.5% of the population checked its box. The United Nations reports that many Afro-Colombians historically identify with their geographical community, making political organisation difficult.

The lack of Afro-Colombian recognition continues in even leftist social movements. On June 15, more bogotanos returned to the streets. These protests, which made their way to El Centro, had #BlackLivesMatter wrapped up in a large list of demands. Some called for better government support for families and individuals barely making it through the pandemic’s economic consequences. Others repeated demands to end corruption at the national level, echoing calls seen during the paro nacional. But groups of protesters, including members of Proceso de Comunidades Negras (PCN) and Matamba, a Black feminist organization, maintained their focus on Black lives, demanding justice for Anderson and other Afro-Colombians. Like previous marches pre-pandemic, many denounced ESMAD and local police’s violent responses. Photographers captured a gang of neon yellow-clad police officers kicking and surrounding a young person on the ground. Government forces launched tear gas and detained several on the streets.

Related opinion piece: Who polices the police in Colombia?

Mayor Claudia López condemned the actions of protesters for violating strict quarantine rules. “It’s evident that those who called these protests in the middle of a pandemic have more interest in destabilising health and democracy and protecting it.” Right-wing US officials have cast similar critiques on Black Lives Matter protests; US-based protesters have responded with signs reading, “We are risking our lives because our lives are at risk.”

The question remains as to whether or not future anti-government, anti-brutality movements in Colombia will centre Black lives. Already, the June 15 marches saw many protesters launch a race-neutral attack on the government, failing to name disproportionate effects of violence on Afro-Colombian communities. At its core, the Black Lives movement in Colombia questions the nation’s self-conception through a homogenous, mestizo, multicultural identity. As protesters and Afro-Colombian scholars alike have noted, ignoring race and ignoring Blackness allows violence against Afro-Colombians to continue unchecked by both the political left and right.