Two of Bogotá’s most iconic buildings, the Torre Colpatria and the Aseguradora del Valle building, Las Residencias Colón sandwiched in between.

Although they may often go unnoticed, some of Bogotá’s most noteworthy buildings offer an intriguing insight into the capital’s past, as Chris Erb and Eduardo Cote discover.

To reach downtown Bogotá from the north, it’s almost a must to go through a place you’ve likely never considered, despite its importance: a small plaza which is located to the west of Carrera 13 at Calle 26. The plazoleta forms a triangle that functions as an intersection, allowing traffic of all sorts to take Carrera 10 south into the city’s core.

Although many people routinely walk or drive through this point, few are aware of the important buildings and spaces brought together in a very small space, as well as this area’s impact on Bogotá’s 20th Century urban development history.

The plazoleta itself features a circular sandstone basin with a marble sculpture of a nude woman in the centre. From the heavily trafficked Carrera 10 that passes by, one can see an unusual curved white silhouette that rises to the sky, and in the background a “luminous” tower that can be seen far and wide.

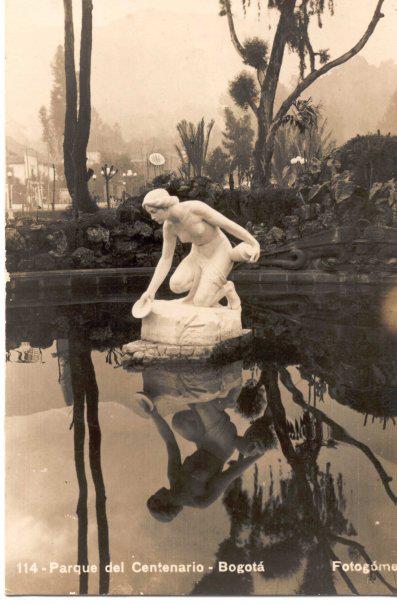

The Rebeca arrived from the town of Pietrasanta, Italy, to Bogotá in 1926, making her the first nude female sculpture to be displayed in a public space in the capital. Only in 2012 was the identity of her real sculptor, Tito Ricci, discovered and in the year prior she was moved from the Parque Centenario (of which today’s Parque de la Independencia is just a small remaining part) to be placed in her current, isolated home. Here she is abandoned and occasionally mutilated, painted and, very often, caressed by the streets’ dwellers.

- The Rebeca in her original location at Parque Centenario, 1943.

- Tito Ricci’s Rebeca in the plazoleta in front of the landmark Aseguradora del Valle building, with the Colpatria building in the background. Photo: Eduardo Cote

Surrounding her is Neptune’s basin (currently more for garbage than water) where the Rebeca, somewhat sadly, collects water that isn’t present with a bowl and a sculpture of Poseidon’s face that watches her from behind. This whole piece, made in 1885, forms the central axis of the plazoleta.

Behind the Rebeca, rising like a great parabola that leads to the sky, is the building whose distinctive shape everyone knows and uses as a reference, but whose name few are aware of: the Aseguradora del Valle building. Built in 1972, this building’s unusual, slide like shape and long horizontal windows that end abruptly at long, curved balconies at the edges have made it an important symbol of Bogotá: no visual depiction of the city’s skyline is complete without it. With a height of 20 storeys and 71 metres, it’s not a particularly tall building considering its prominence. Surrounded by the dingy and relatively deserted backdrop that is the Carrera 10, it’s unfortunate that such a distinctive structure is in fact quite disappointing up close.

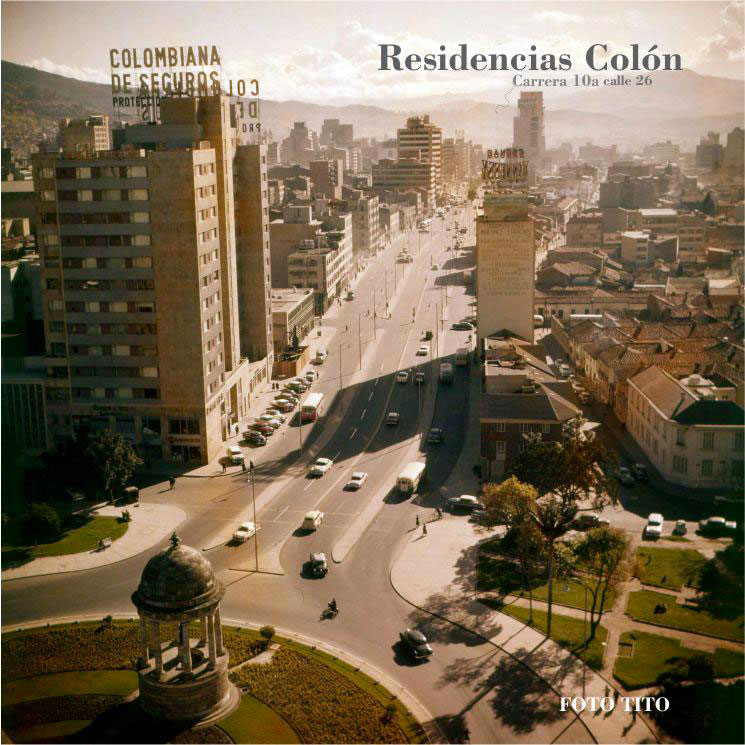

An elevated view of Carrera 10 from before the Aseguradora del Valle building was constructed, Note that today, the TransMilenio station is in front of the Residencia Colón building (where the red bus is located in the picture), the Rebeca is on the small green area to the right, and the monument from the middle of the roundabout is now situated in Parque de los Periodistas in La Candelaria.

On the other side of Carrera 10 is a much less impressive building, but one with an important history nonetheless. In 1947, much of the land on the east side of the carrera was purchased with the intention of widening the street and building a hotel to host a large number of visiting foreigners from 21 countries expected for the upcoming Pan-American Conference. However, only half the building was completed due to the Bogotazo riots – until 1955, when the south-facing half was finally built. The building served as a hotel only until 1964 when, over the course of 17 years, it was transformed into a residential building and renamed Las Residencias Colón. The building, with it’s yellow stone and red brick facade, is quite out of place along this stretch and retains little of the original grandeur (with the exception of it’s impressive two storey marble lobby) it was meant to have.

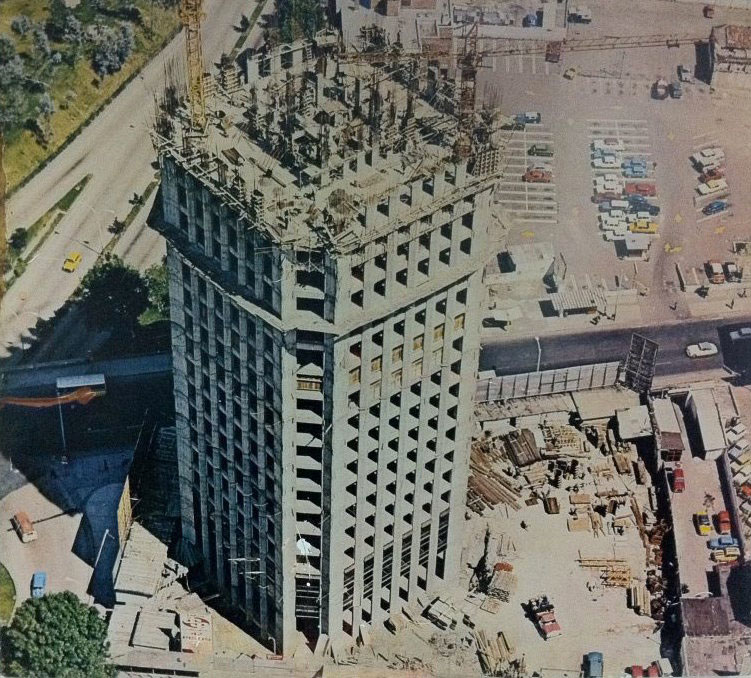

Of all the buildings along this stretch, the Torre Colpatria is by far the most impressive. At 50 storeys and a height of 192 metres, this tower was, from the time of its construction until late last year, the tallest building in Colombia. Upon completion in 1978, it was the tallest in Latin America and is still the fifth tallest in the region. An attempt on its title as Colombia’s tallest was carried out in 2007 by a building project called Torre de la Escollera in Cartagena, but it was demolished before completion due to high winds going up against shoddy construction. When the nearby BD Bacatá on Calle 19 was recently topped out at 260 metres, it took Colpatria’s place as the city’s tallest building. However, the Torre Colpatria is still an important symbol of the city. Its simple, vertically-oriented outer columns make it look strikingly tall and imposing, and the thousands of LED lights installed on all four sides make it impossible to miss after dark. It’s hard to imagine the centre of Bogotá without it.

The Torre Colpatria under construction in 1979.

In the shadow of the Torre Colpatria sits a small modernist box-like building that was once the Gran Salón Olympia. Now an annex of the Torre Colpatria, the Olympia was the first cinema in Bogotá. Built in 1912 by two Italian brothers, the Salón was pivotal to the beginnings of the Colombian film industry, since many local and European films were shown here. The original Art Nouveau facade was replaced in 1945 by the current modern style in vogue at the time, which mirrors the modernist buildings that surround it. The only evidence of its past use – the last film was shown sometime in the 90s – is the overhang above the front entrance that was once a marquee.

So next time you pass the threshold from the Centro Internacional into the centre, make sure to take a moment to consider the buildings and a lonely lady overlooking the highway. While none are particularly beautiful, they all have a story to tell.

By Chris Erb & Eduardo Cote