A lot of people look down upon Venezuelan migration. But many of us have similar stories and situations – more empathy is needed.

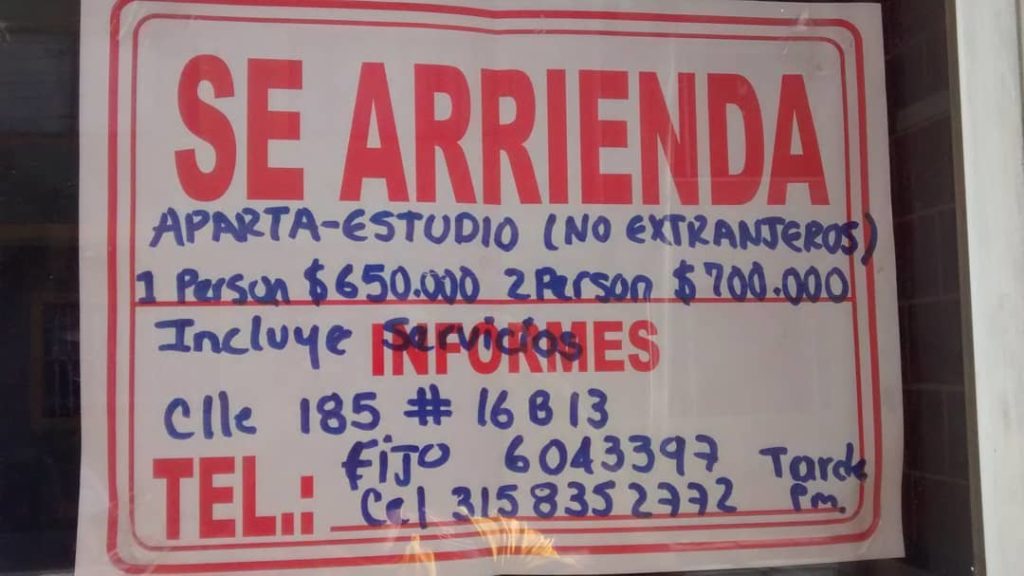

Imagine that you saw a job offer in Bogotá saying that Brits weren’t welcome to apply. A certain amount of outrage, surely. Now imagine a sign in the US saying that only American citizens would be considered. Believable, if illegal, and still a source of outrage. Well, here in Bogotá, signs discriminating against Venezuelans are becoming more frequent. If you’re not Colombian but live in Bogotá, this should worry you.

In the discourse about Venezuelan migration in Colombia, a fair few non-Venezuelan migrants seem to think they’re different. These people often seem to view themselves as being somehow good for Colombia, whereas the Venezuelans are somehow problematic. Expats, they call themselves, to disguise their status as migrants.

The term expat is freely used, but often wrongly. Generally, an expat is someone who plans to leave, who doesn’t put down roots, who is temporary… And then there’s the unspoken and ugly finish to that list … Who’s also white, who is rich. So a lot of people that should be termed as migrants hide themselves under the respectable cloak of being an expat.

Related: Previous big topics from our columnist

The image of a migrant is often that of a poor person, often with dark skin, often from a country seen as being poor in comparison with others. They’re characterised as people in search of riches, as opposed to those fleeing persecution. However, there are few, if any, rich-world migrants to Colombia who are fleeing persecution. All the rich-worlders here are in search of economic benefit or using their economic status to piss about and have a good time. That’s simply not true of the latest wave of Venezuelan migration. Most of these people have abandoned their possessions and travelled with only the most basic things they can carry.

We all have different migrant stories. Some of us came in search of adventure; others came in search of better opportunities. Is there so much difference between someone like myself, who saw the UK as a place with stagnating growth and chances; one with ossified social structure, and a recent Venezuelan migrant who looked at the fracturing Maduro regime and decided there was little for them at home? In degree, certainly. In principle, not so much.

So why do so many migrants avoid the label? Some of it comes from a denial of their life plans, an insistence that they will be leaving soon. Some of it, though, comes from a need to not be poor or simply to see oneself in a different light. Venezuelan migrants are often from very poor backgrounds. This fits with our idea of poor migrants. Migrant status has many negative associations.

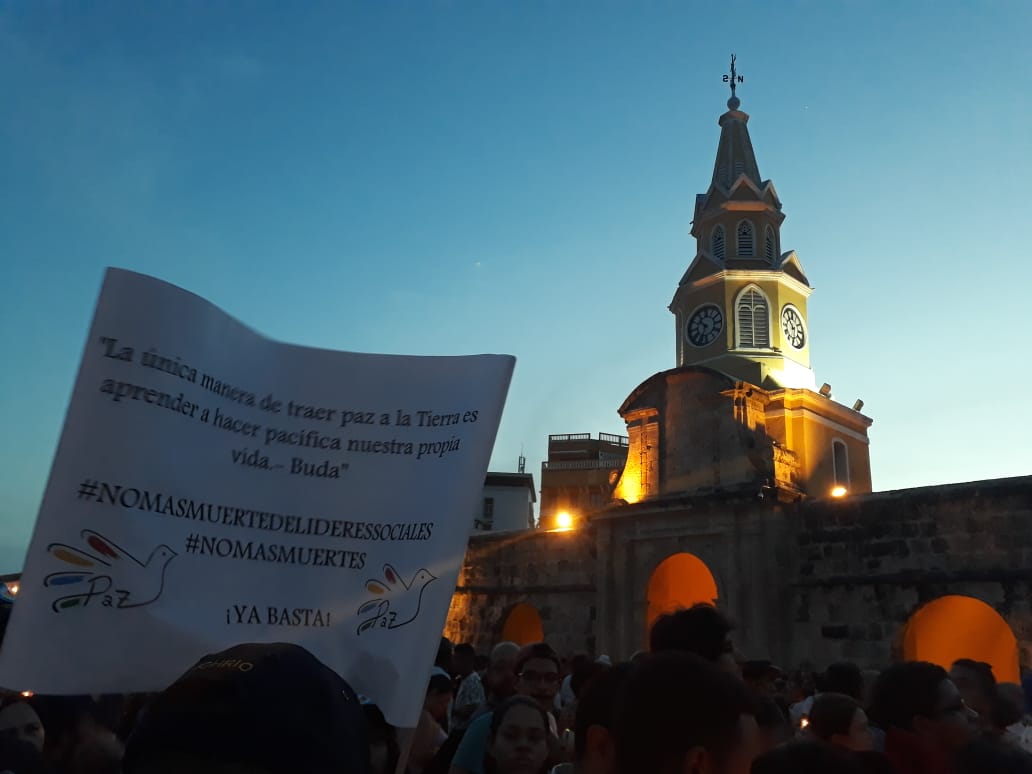

Somewhat predictably, there’s been a wave of racist reaction to the recent arrivals from Venezuela. It’s something that’s understandable if not acceptable – Colombia is not equipped to deal with such an influx, and it’s the poorest communities in the country that take the brunt of it. It’s galling to see foreigners here joining in, though.

There’s no doubt that many of you migrants from the global north who are reading this are generally treated well by Colombia and by Colombians. It’s certainly been my experience here. It’s also not the experience for many Venezuelan migrants. A burden falls upon us as fellow migrants with a more audible voice to stand in solidarity with those who don’t have as many advantages.

What can you do? You can get involved with schemes to help other migrants. You can stop calling yourself an expat if you’re really a migrant. You can give money and help to those that need it. You can call out racism and discrimination when you see it.