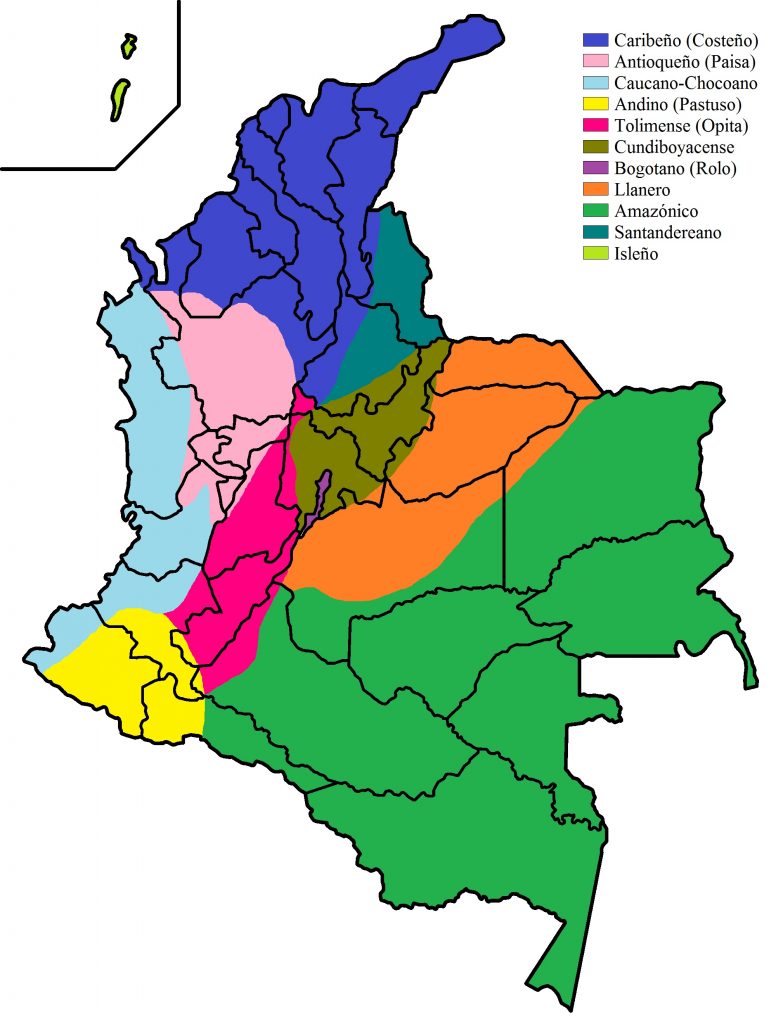

The differing regions of Colombian Spanish

Can you tell your Costeño from your Chocoano?

From the singsong of the Caribbean, through the Antioquian lilt and all the way to the Ecuadorian-like Spanish spoken in Pasto, Colombia’s different accents are as varied as its people. The mountainous terrain has created physical barriers that have caused regional culture and language to diverge in a multitude of ways.

Similarly, the variety of Colombia’s inhabitants – white, mulato, black, indigenous, and everywhere in between – have put their own spin on an already fragmented common language. In fact, it’s not uncommon to hear people from the capital complain about having a hard time understanding their hosts when travelling in other parts of the country.

Whether this is because the Spanish spoken in Bogotá is “clearer” than others (as many capitalinos would have you believe) or simply because Colombian media broadcasts typically bogotano accents to the rest of the country, the reality is that understanding Colombia’s different accents can be a bit of a head scratcher, even for native speakers.

Beyond the different varieties of Spanish, there are also over 60 indigenous languages falling mainly into the Chibchan, Tucanoan, Bora–Witoto, Guajiboan, Arawakan, Cariban, Barbacoan, and Saliban language families peppered throughout the country. Moreover, there are the two distinct Afro-Colombian creole languages that are the criollo palenquero spoken in the San Basilio de Palenque and the criollo sanandresano, spoken in San Andrés and Providencia (where English has official status).

Alas, the distinct languages will have to be a topic for another time. For now, let’s focus on the local variants of Castilian. Colombian phonological dialects can be divided into 11 broad groups, corresponding to their geographical origin.

Rolo

Spoken in Bogotá, rolo or cachaco, is distinguished by its formality and the use of the pronoun usted even among family members and close friends. All letters, including syllable-final /s/ and /d/ in the -ado endings tend to be pronounced.

Cundiboyacense

As the name implies, this is the variant spoken in the Cundinamarca and Boyacá plateau and is one of the oldest dialects of the country, having been a hub of activity in the colonial era. It is common to refer to others as sumercé, derived from su merced (your grace). This once overly-formal expression is now used in the same way as usted and is conjugated in the same fashion.

Paisa

Perhaps one of the best-known Colombian accents, paisa is heard throughout much of the coffee-growing region including Antioquia, Risaralda, Quindío and Caldas. One of its most distinctive features is the phrasal intonation that drags out the end of a sentence in a most peculiar tonal rise and fall. The /s/ is pronounced slightly more like an /sh/, giving the accent an almost whisper-like feeling when spoken quickly and quietly, as it often is. A noteworthy grammatical difference is the voseo, or the use of the pronoun vos, in most informal situations. Thus, instead of ¿Qué quieres comer?, one might ask ¿Qué querés comer?

Valluno

Spoken along the Río Cauca valley, the valluno (also known as bugueño or caleño) accent resembles the paisa in its use of the voseo in every-day speech. It also makes use of the jejeo, which is the change of an /s/ in between vowels to a /h/ sound. Thus necesitar is nehesitár and los hombres would be lohómbres. Oddly, all other /s/ sounds are actually very strongly pronounced. Finally, the /n/ sound at the end of a sentence is often changed to an /m/ sound: tren becomes trem and pasión is pasióm. Common expressions include pachanga (party) and filler words such as ¡ve! and ¡mirá ve!

Costeño

Spanish from the Caribbean coast tends to get lumped into one broad category. However, this is a bit of an oversimplification. The accents from Barranquilla, Cartagena, la Guajira and the interior coastal regions are all considered sub-dialects of the broader costeño classification. And while people outside the region may have a hard time picking them out, you’d risk offending a barranquillero if you told them they sounded like they were from Cartagena, and vice-versa.

The most defining characteristic of the region is the weakening or omission of final consonants in a word, as well as the aspiration of the s at the end of a syllable, which changes from an /s/ sound to a weak /h/. So fósforo (match) will become fo’foro, los amigos is lo’ amigo’ but the s in Santa Marta would not change, since it’s at the beginning of the syllable. Some other letters may be omitted as well so that Cartagena would be pronounced Ca’tagena and verdad would be ve’dá, a trait shared with Cuban and Dominican Spanish.

Related: More tips on how to improve your Spanish.

Finally, Spanish from the coast differs in that the tú pronoun is widely used even in formal situations or between strangers (instead of usted). Common expressions include ajá (yes), eche (interjection of disbelief), mira pue’ (you don’t say), and nombe (no).

Santandereano

In Santander and Norte de Santander, you will rarely hear the pronoun tú, as usted dominates in almost all formal and informal situations. This, alongside their staccato speech, makes the accent sound a little angry, or as the locals would say; arrecho.

Llanero

This accent is spoken throughout the Colombo-Venezuelan plains and can be heard in the Meta, Casanare, Arauca and Vichada departments. Its most notable feature is the indigenous influence, with many native words having been incorporated into the regional language. Another distinctive element is the weakening or total suppression of the redundant /s/, such as in los caballo.

Pastuso

The accent in the Andean department of Nariño is closer to that spoken in Ecuador, Peru or Bolivia than to many of its Colombian counterparts. This is another region with strong indigenous influence, with many common words adopted from Quechua language, for example: achachay for cold, cuiche for rainbow and guato for small. The /r/, like in Chile, is assibilated – that is, it’s made to sound more like a hissing sound that you would normally expect to hear. Vowels are also weakened to give more emphasis to the consonants, and like in the interior, the /s/ is never omitted or weakened.

Opita

In Tolima and Huila, people are known for speaking very slowly. Another characteristic is the change of the common hiatuses to diphthongs so that pelear will be peliar and peor becomes pior.

Chocuano

Last but not least, the Colombian Pacific coast, with its heavy African influence and extreme isolation, has developed a unique accent that borrows heavily from its ancestry in intonation and rhythms. Like in the Atlantic coast, the final /s/ sounds are often omitted so estos señores becomes eto señore.