With Bogotá Pride 2025 coming up fast, we took a trip to the country’s only museum of LGBTI culture.

Closeted away in a backstreet of Santa Fe is the Museo Stonewall, or Museo LGBTI, of Bogotá. With Pride on this weekend (Sun 29th June), it seems an apposite time to visit. It’s the only museum of its type in Colombia and a mere ten years old.

In recent years, Bogotá has taken huge steps towards acceptance of LGBTI (we are using this acronym in line with the museum name) culture and communities, both societally and at an official level. The local government heavily promotes gay tourism in Bogotá and places like Parque Hippies openly display state-endorsed rainbow flags.

Pride in recent years has exploded, growing rapidly to an enormous street festival celebrating diversity of sexuality in its many guises. Correspondingly, acceptance of homosexual relationships has come on in leaps and bounds, even if some issues remain.

No surprise really, as the city has one of the biggest LGBTI communities in Latin America, with Chapinero from the rough area around Teatrón (the continent’s largest LGBTI club, even if it is increasingly hetero) to Hippies known informally as ‘Chapigay’. Gay bars and saunas abound, as well as a lesbian bar.

Somewhat unbelievably, the museum receives zero funding from either national or local government, meaning it is reliant on handouts and visitors. I’m shown around by founding director Rubén Darío Gómez López upon arrival.

Inside the Museo LGBTI de Bogotá

Colombia generally does smallish museums with passionate owners very, very well and this is certainly no exception. However, it’s somewhat labyrinthine on the inside, with room after room opening up as we walk around. There are 14 in all, spread across three floors.

There’s clearly a heavy focus on education, with Rubén patiently and comprehensively explaining each room and exhibit. He falls easily into what seems like a well-worn patter and is at pains to go into detail into every aspect, not assuming any prior knowledge.

The museum takes its name from the famous Stonewall Inn in New York, a globally-recognised symbol of the struggle for LGBTI rights and a name used around the world for similar organisations. It’s set inside a former gay sauna, now repurposed for making a visible communities that were traditionally hidden in Bogotá.

Ruben underlines the importance of maintaining a historical record, noting that many figures from the past were queer, even if not recognised. “Michelangelo, Alexander Von Humboldt and even a founding father of Colombia, Francisco Caldas,” he names, although it’s worth noting that there’s debate around all three.

There is a small corridor exhibit on the intersection of BDSM in Colombia and the LGBTI community, before passing into the Trans room. The positioning of the room first feels like a statement and Rubén confirms this, noting that “the T is absolutely part of the movement.”

There are homenajes to leading trans activists in Colombia, such as Deisy Olarte and Laura Weinstein, as well as exhibits that illustrate the challenging situation for trans people in Colombia, both male and female, which has been a political football at times. A beautiful statue named ‘Mariposa’ takes the centre space, elegantly symbolising change, rebirth and development.

A powerful artwork to the side represents Luis Álvarez, a teenager from Sincelejo, Sucre, brutally mutilated with a machete solely for being ‘too feminine’. Neither is this a thing of the past, as it carries echoes of the Sara Milleray case recently in Antioquia. Rubén tells me that the average life expectancy for trans people is just 37, less than half that of other Colombians.

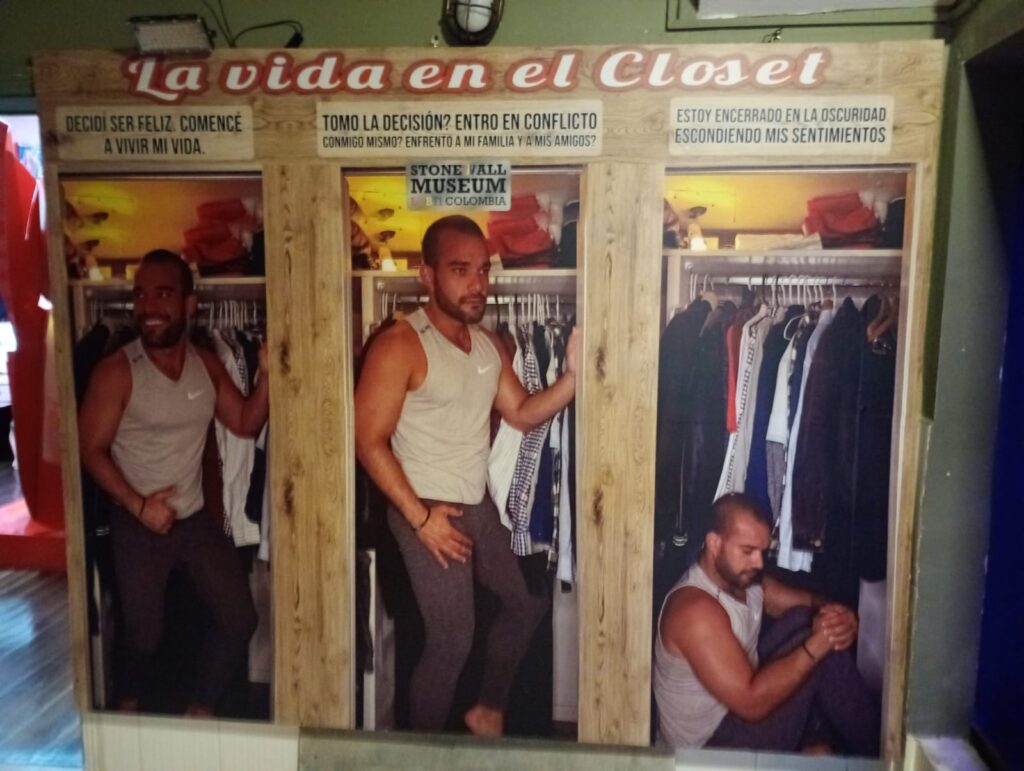

Next up is a triptych of photos that represent perhaps the most culturally important event in many LGBTI peoples’ lives: coming out of the closet. The model in the photo moves from sadness, through nervousness and finally to happiness. Rubén says that we need to “respect people at every stage of the process, as everyone is different. There are still many people that take [their secret] to the grave.”

The reason why may lie on the stairs: a copy of the old penal code, in force all the way up to 1980, lies open at the page with artículo 329. That stated between six months and two years in jail for men engaging in homosexual acts

Upstairs, a pair of rooms are dedicated to lesbian women and gay men respectively. Rubén reckons that there are “much more lesbians than gay [men] in Colombia,” noting that “they are not always open and often stay in the shadows.” It’s certainly not what is most visible when one thinks of Chapinero and Parque Hippies.

A touching room is dedicated to marriage – a totemic issue within the LGBTI community. For many, marriage symbolises societal acceptance of a relationship but has only recently been extended to all of society. A selection of flags and dates shows just how recent this has been for much of the world.

A display of books shows the diversity of Colombian and international academic and fictional literature on LGBTI issues, while a larger room presents images of Colombians and foreigners who are either openly LGBTI or have done a lot for the community, such as Brigitte Baptiste, Sir Ian McKellan, Angélica Lozano and many more.

The museum certainly pulls no punches in presenting LGBTI culture and avoids the trope of presenting LGBTI issues as asexual. Some of the sculptures are explicit (in every sense) celebrations of sexuality. There is a whole section dedicated to cruising as part of the gay (male) scene, particularly concerning Cuba and its beach scene.

While the regime was often repressive, imprisoning gay men, “state repression cannot eliminate the desires of the people,” says Rubén. The exhibition shows graffiti that is partially erased, encapsulating how the Cuban government literally tried to make the gay community invisible by painting over the words.

Why Bogotá Pride 2025 matters

While Articulo 329 of the old código penal may be in the past, homophobia and transphobia most certainly are not. Rubén says that “in laws, in norms, things are good. In capital cities and the interior of Colombia things are generally ok. But in the regions and the exterior it’s not the same. Machismo and homophobia are common.”

It’s worth remembering that one of the reasons the LGBTI community is so large in Bogotá is precisely because many people from the community have fled repression and hostility elsewhere in the country. There are still many who live a double life between the capital and their birthplace.

“In institutions such as the army, the churches, even families” Rubén continues, “often it is [closeted] people that are disguising their homosexuality who are the most anti-gay in their rhetoric, in their speeches. What they show to the world is not who they are.”

Indeed, even as much of the city is celebrating its large LGBTI community on Sunday’s march, there will be counter-marchers protesting against Pride and what it stands for. These might be much smaller, but serve as a reminder that not everyone is in favour of the cause.

Rubén acknowledges a difficult time globally for LGBTI issues, saying “It’s not the same as it used to be. We have had many advances, many, but we still need more. Celebrating Pride is to say ‘it’s good where we have come to, but we have to sustain it, to defend it.”

It’s an important reminder that things can change in both directions and that Colombia needs to be careful not to rest on its laurels when it comes to human rights. There has been good progress, but it must be protected and there remains work to be done, for example in the field of adoption or enforcing anti-homophobia laws.

The Museo LGBTI (Carrera 13A #38-60) is open Mon-Fri 9am-12md. Just ring the buzzer and someone will let you in and show you around. Price COP$7,000 as of June 2025. Adults only, as some exhibits are sexually explicit.

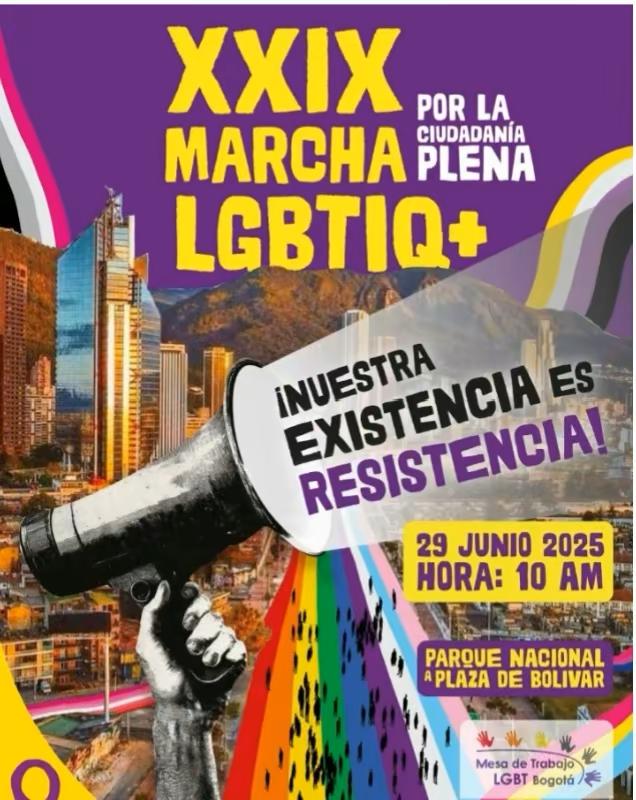

Pride’s main march is on Sunday 29th June on the Séptima from a flexible 10AM around the Parque Nacional by the Rita statue on 39th. The Trans march is the following Sunday.