The never-defined project of Paz Total appears to have had little to no effect on violence in Colombia, with things getting markedly worse recently across the country.

2025 has been a violent year for Colombia so far, with the attempted assassination of senator and pre-candidate for the presidency Miguel Uribe Turbay the most high profile incident. Away from the capital, three regions are descending into chaos.

This stirs unwelcome memories for many Colombians who lived through the violence around the turn of the century. Then, large parts of the country were impassable and both high profile assassinations and street-level murder all too common.

For a government that came into power with a mandate for change, this has to be seen as a failure. The administration promised ‘Paz Total’, a slogan that sought to calm the often troubled waters of Colombian politics, especially in rural zones.

More of an idea than anything else, ‘Paz Total’ was a response to the violence that has dogged Colombia over the years. Previous president Iván Duque had faced mass protests that often turned violent, there were active rebel groups across the country and a shakily implemented peace process.

This meant that many Colombians were eager to see an end to the various conflicts and a strengthening of the ongoing disarmament process of the FARC, previously Colombia’s largest rebel group before signing a peace deal.

When Colombia elected president Gustavo Petro into office in 2022, no one could say they didn’t know what they were getting. After spells as Bogotá mayor and national senator alongside a string of presidential runs, his politics and personal history have long been in the public view.

Just what is ‘Paz Total’?

However, he’s also long been known for being fuzzy on details – and unwilling to compromise either. Paz Total fitted in perfectly with that – a great idea that everyone can get behind, but with no concrete plans or clear definition.

With such a lack of clarity, in the end Paz Total can be applied to everything and nothing, allowing the government to try and evade oversight on its success or lack thereof while simultaneously pegging its name to a range of causes.

The slogan has been unfit for purpose and purposefully vague for a while now, but growing insecurity and violence in the country has got to the point where even partial peace seems ambitious, let alone ‘Paz Total’.

It is little more than empty rhetoric, being wheeled out time and again in the face of events that require real action to be taken. Once again, swathes of Colombia are becoming no-go zones and internal displacement is on the rise.

This all adds up to a worrying sense that the state is losing what little control it had over the country and that we might be sliding back to more violence and conflict. While we – especially in major cities – are far from the levels of the early 2000s, we are moving in the wrong direction with no sign that anything is being done to change course.

Politicians – from all sides – are adept at calling for peace even as they make statements that raise the political temperature. Marches and concerts for peace are organised, but little of note is being done to make any real impact on any of the various fronts that have now opened up in the struggle for ‘Paz Total’.

Cauca in chaos

This weekend saw a dramatic uptick in terrorist activity in the rarely calm southeast of Colombia, with a spate of 24 separate terrorist attacks. Eight people were killed and dozens wounded as rebels put on a deadly show of strength.

While the most dramatic attacks were car bombs, there is a growing sophistication in these attacks, with drones increasingly being used. While this has yet to become commonplace in Colombia, the potential is there for this to be a worry for years to come. With dozens of murders of military figures in 2024, a lid needs to be put on this.

Neither national nor local government has been able to provide much sense of stability to the southwestern region for years now, with Buenaventura, Tumaco, Cali and Palmira regularly seeing high murder rates and conflict.

The mayor of Cali, Alejandro Eder, drew clear parallels with the horrors of the past. In a statement at an emergency meeting, he said that he didn’t want a return to the 1980s, emphasising the gravity of the situation. The Medellín Cartel may be more famous globally, but the Cali Cartel was every bit as deadly, if not more so.

Guaviare locked down

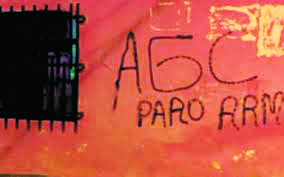

Territorial disputes between rebel groups in the llanos orientales have led to the announcement of a lockdown for the week in Guaviare department. Iván Mordisco’s group of FARC rebels are clashing with those of Calarcá, leading to a rebel-imposed curfew throughout much of the region.

The two leaders both command ex-FARC blocs that have rejected the peace process and taken up arms, but do not share the same ambitions. With both tussling for control over Guaviare, it is regular campesinos that are quite literally caught in the crossfire. For at least the rest of the week, there are strict conditions on who can travel and where.

Embarrassingly, this makes it clear that the Colombian armed forces have simply lost the ability to control large swathes of Guaviare, including relatively close to the departmental capital. The department, which hosted Petro himself only this weekend, has in recent years come on to the tourist map thanks to its stunning ancient rock art, nature and indigenous cultures. All that will now be up in the air once more.

Catatumbo in chaos

Since January, the Catatumbo region in northeastern Colombia has seen increased activity from the Frente 33 FARC dissident group and ELN. Both groups have attacked the Colombian armed forces as well as each other.

Attempts to negotiate ceasefires went nowhere and the death toll in the small region tops 130 in the last five months. The Defensoría counts over 60,000 people displaced in the space of just three and a half months as well in what they call the biggest humanitarian crisis in the region this century.

Worryingly, the months of conflict have shown a particularly high level of non-conventional tactics. That covers drones as mentioned above, operating close to schools and densely populated areas, use of anti-personnel mines and sexual violence, among others.

Peace talks going nowhere

Petro has made nominal attempts to open peace talks with a range of groups, from drug gangs such as the Gaitanistas to FARC dissidents to the ELN. None have got very far though, with others falling into complete disarray.

This isn’t entirely the government’s fault – negotiations require both sides to act in good faith and make solid commitments, which hasn’t been the case. However, they’ve only been able to organise a few shaky ceasefires and haven’t got any firm agreements, let alone anything signed and sealed. After three years, that’s telling.

Feminicide rising

Over 700 women were killed in gender-based attacks last year, with numbers likely continuing to remain high. This was allegedly a priority point for the incoming administration, but little concrete has been done since assuming power.

More worryingly, major figures in the political movement have been accused of not taking womens’ issues seriously at all, with high profile resignations such as Susana Mohamed. She took the unusual step of explicitly saying she could not stay in the government with certain figures as a feminist.

Crime up in cities

While Bogotá was reporting official decreases in overall crime rates, murders are up year on year, as is violent crime in general. The latest figures for 2024 are grim reading. The old adage is that homicide gives the most realistic idea of how bad things are, as it’s harder to fudge the numbers for murder compared to many other crimes.

Perceptions of crime are certainly not down, with few people believing official figures. This adds to a growing sense of instability and a lack of control in urban areas throughout the country. Both violence and robberies are up, with fears that the numbers on paper are merely the tip of the iceberg in reality.

Put together as a panorama, Colombia isn’t in a good place in terms of safety and security, with the state unable and unwilling to bring order to various different regions. If this continues, it is hard to see how any peace, total or otherwise can be achieved.

With elections looming, it’s easy to imagine that there will be hardline candidates promising crackdowns following the Bukele blueprint. With many citizens increasingly desperate for a semblance of order, that may well be popular at the ballot box – as it was for former president Álvaro Uribe Vélez.