Oliver Pritchard explores ideas of memory and forgetfulness with curator Cristina Lleras

Who, what, where, when

The Museo Efimero de Olvido brings together 46 projects from artists working in a vast array of mediums, exploring the topic of forgetting. Up-and-coming artists share the space with more experienced, well-known names, with the art itself taking centre stage.

Kicking off on August 3, the exhibition will run until September 5 in a number of buildings in the Universidad Nacional. There are also displays in the Casa de la Cultura in Duitama, Boyaca, if you happen to be up that way. Open from 10am-7pm, Monday-Saturday.

In addition to the exhibition, there are a host of talks (every Wednesday) as well as film screenings at a variety of times.

Guided tours take place on Wednesdays at 3pm and 6.30pm and on Saturdays at 11am. Be sure to fill out the form online to have tours tailored to your group.

For detailed info on the specific artists and their projects, as well as all the spaces which will host displays, and the times/dates of the talks and film screenings, visit the website: www.efimero.org

Facebook: /museoefimero

Twitter: @museoefimero

Museums are often thought of as entirely connected to memory, vast warehouses that contain nought more than recollection and reminders.

The Bogota Post had the immense pleasure of being invited to talk to the curator of the Museo Efïmero del Olvido, or the ephemeral museum of forgetting.

Upon arrival at the Universidad Nacional, we were led through the winding paths of the campus by an enthusiastic young student who took great care to explain the project and point out venues where the exhibition will take place.

Our meanderings eventually brought us to a stop at the graphic design building, wherein we were warmly welcomed by the effervescent Cristina Lleras.

She shows us around the first room and explains the concepts of the artwork before ushering us towards a workbench that will serve as a temporary desk for the interview.

Everything is laid back and casual, a refreshing break from many artistic endeavours that seek higher ground and the airs and graces that go along with it. Despite an extremely impressive CV, Cristina is self-effacing and speaks with candour.

She starts off by explaining why she wanted to do something like this.

“I had worked for the Museo Nacional for 12 years before I left. The pieces and places are wonderful for sure – and the building is amazing – but I had started to see them as obstacles for me. I read museum studies at Uni, and I found it quite traditional, quite conservative. So, I wanted to try something new, an alternative idea of a museum, one with no collections, no buildings, no permanence.”

Changing the way we look at museums

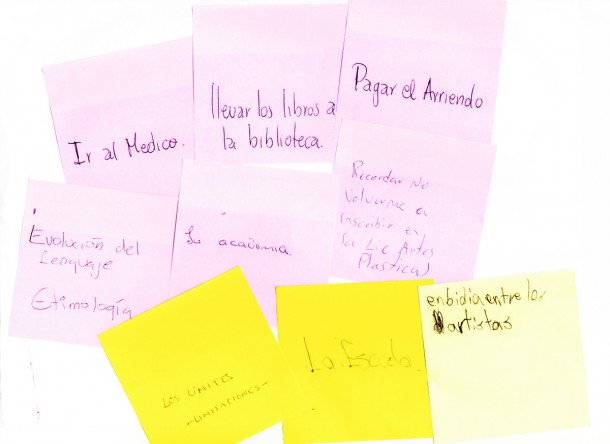

It certainly sounds different, so how will this change the way we look at museums, I wonder? Cristina leans forward, her intense eyes shining as she elaborates for us. “It’s the pedagogy of oblivion. We all know that learning and memory are intimately connected, that they work together. But there’s another interesting point, that we need to forget certain things, or that we can understand some things better if we forget others. It’s vitally important that we understand what we need to forget, or what we can forget.”

She notices my glazed eyes and eases up, “Well, an example would be dates of birth of artists. It’s not usually very useful and rarely gives you any insight into the art. Worse, it’s a distraction from the artwork itself, which is really the thing you should be concentrating on. Understanding the context of artworks is one thing, but it shouldn’t be an exercise in memorisation, and you don’t need to know exact dates. However, all museums do exactly this. Next to the art is a sign telling you what to think.”

She elaborates further on the theme of the gallery atmosphere, “Interaction is not just pushing buttons. That may work in a science museum, but it needs to be different in a gallery such as this. It doesn’t have to be interactions with the pieces, but with other people. Social interaction. Museums are social spaces, we shouldn’t forget this. Only a few people go to museums alone, studies have shown, yet almost every institution frowns on talking, prefers silence and a stereotypical way of seeing the art. Actually, I’m encouraging people to talk and to discuss. I want to hear debate about the meaning of the art. I want people to forget what they expect to see, to forget the norms of art appreciation, to forget that it’s a museum.”

Different approach to space and place

One of the principal differences of the museum is the approach to space and place. The exhibition is spread far and wide among the elegant grounds of the Nacional campus and each space will have a different atmosphere, although they follow a common thread.

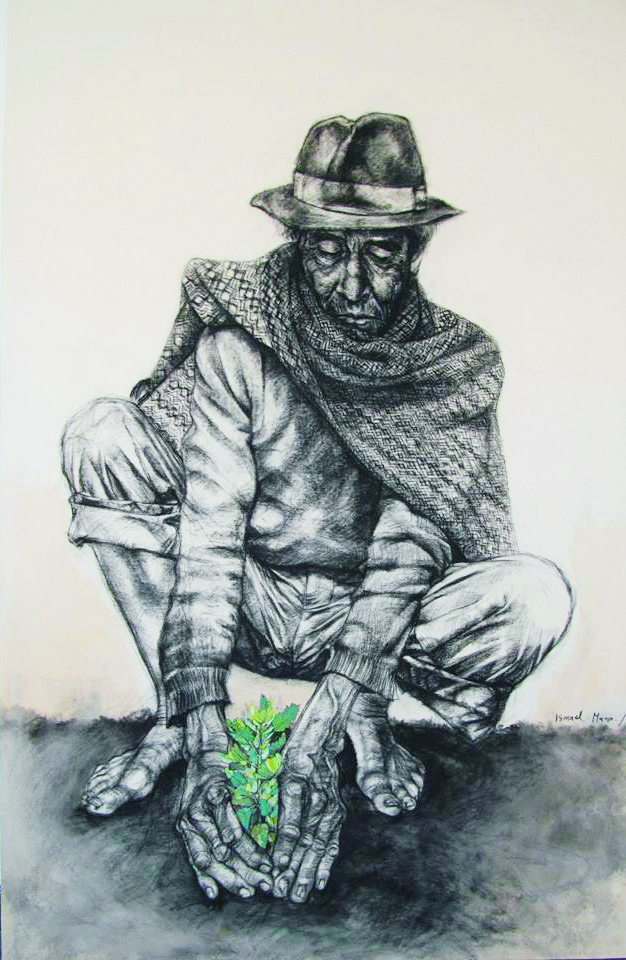

For example, the works in the Museo de Arquitectura are fiercely critical of the modern political and industrial world, whereas the edificio SINDÚ features works that celebrate a positive reflection of the rural world.

Although complementary, they display different methods of dealing with a similar idea.

Cristina explains that this is connected with the myth of self-representation, so prevalent in Colombia: “Why do we need this? What do we remember, and what do we choose to forget? Questions like this make you realise that you can’t think about forgetting without also considering remembering.”

The artists

The artists involved are drawn from the full spectrum of artistic disciplines, from painters and sculptors right through to audiovisual artists. Cristina describes it as having “no narrative there, but it is a story. We’re featuring some very varied artists, it’s a really intergenerational show, with some established artists alongside some absolutely new blood. As I said before, the art is centre-stage, so I don’t want people to focus on the artist but the artwork.”

An intriguing idea, but don’t worry, the names will be available online if you are interested in following any of the artists further. “The artists would kill me if I said you could forget them!” jokes Cristina, although with an edge of steely seriousness in her eyes.

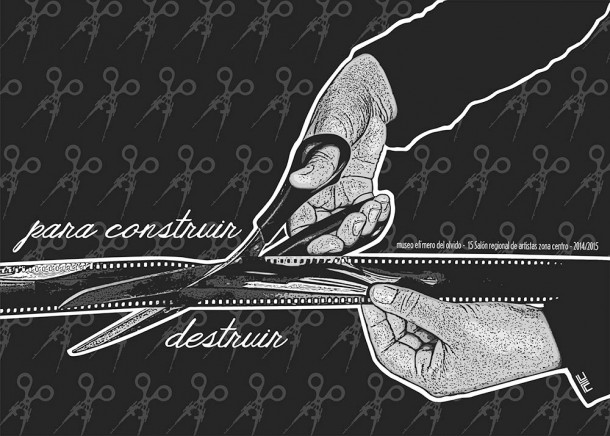

The central ideas of ephemerality and forgetting piques the interest, and the artists have interpreted it in different ways. In the central plaza of the post-grad building, also known as the Salmona, there will be an enormous picture comprised completely of seeds. This being Bogota, eventually the rain will come and destroy the picture, wiping it away, only to be reconstructed. As one picture is forgotten, so another is born.

- José Ismael Manco Parra – Intercambio de semillas y pensamiento

- Camilo Sabogal Bernal – Eram Quod Es, Eris Quod sum

- Miguel Canal – Esta es mi vereda

Forgetting and remembering

In the documentary La Siberia, to be shown on August 8 and 16, recollections of a cement factory are recounted, although they contradict each other in part, showing how we forget, and what we remember, forcing us to consider the idea of how memory functions.

A sewn map of Chapinero will be shown in the Museo de Arquitectura Leopoldo Rother, weaved into life with all the parts yet to be developed left green.

These green spaces represent those that have been forgotten by developers, that have been, in their way, abandoned.

The library will explore ideas regarding our reliance on books and documents when considering the past. Although these are powerful symbols of memory, so too does the written word lie at times.

“It’s about a narrative,” says Cristina, “and how we construct them. Consider the work ‘Lenin arrives’. It’s an absurd idea, that a historical figure such as Lenin would arrive in contemporary Bogota, but it allows us to construct a new narrative, thus challenging ideas of memory and how that influences our concept of truth. The Sietecolores project has similar ideas too.”

In the modern world it feels to me as though we have an obsession with cataloguing and archiving everything we see and do, from a moderately OK dinner to average nights with friends.

As the youth shuffle through life with their trousers around their ankles, gazing moronically into their google-twitter-phones, I wonder if this exhibition is a deliberate response.

“Do you really think that?” challenges Cristina immediately.

“I disagree, I think that constant need to photo and record is more to do with a register of experience. It’s about the present, not a memory of the past. Those things are meant to be forgotten, ephemeral by nature. Think about a shopping list, for example. When we create one, the duty of remembering goes to that piece of paper and we are absolved of the responsibility. Monuments, photographs, yes, even status updates provide us with a memory, so we no longer have to remember.”

She’s not finished though, as she leans in to expound her theories.

“We live in an era where so much weight is given to the present. So many museums are popping up all around the place and we seem to have an angst about forgetting, that we might somehow lose ourselves in this drive to advance further and further. Questions of the past might yet be pertinent.”

Future and permanence

The idea of impermanence permeates the show, and Cristina tells us that the exhibition will be ephemeral and fluid in some aspects throughout the time it’s on.

“Some works, yes, will be impermanent even in the short time we have! For example, Camilo Parra will be painting over existing paintings, thus changing and manipulating them throughout the duration of the museum, and close by, Camilo Sabogal will be changing photos as we go along. Consider even the works of this room, by Miguel Canal. He’s showing stills from his Grandad Gonzalo’s collection of film. But these films have been attacked by fungus, so they are not true memories, or not exact. He’s also displaying some of the films as films, and that’s interesting, because films are always manipulations of memory, and memory itself is also a manipulation.”

What of the future, I wonder?

Cristina is clear, “I hope to do this again, to continue the idea, but it will never be the same.”

She adds, “the artworks may be the same, but not the museum itself, that needs to be precarious and fragile: that’s the point of it. So we might change and have different forms or a different format, artists or places, but always keeping this same idea of ephemerality and impermanence.”

Finally, for those of you wondering or puzzled, Cristina gives her own opinion of just why you should come on down to what should be an exciting and interesting project.

“Because everyone has a relation with the past in some form. The artists propose their ways of dealing with and reading the past and hopefully all the visitors to the exhibition can recognise or see new ways of remembering or forgetting. It’s really conducive to visits from groups too, friends or family – remember that I want this to spark up discussions and debates! It’s important that we don’t let the past overwhelm us…we can’t remember absolutely everything!”

Powerful final words, although I would caution you to remember one thing – to go to this exhibition!

By Oli Pritchard

Photos: efimero.org